Climate hawks don’t have much to celebrate after the midterm elections, which saw the defeat of several clean-energy champions and the election of a wave of Republican flat-earthers. The Midwest is now almost as dominated by Republicans as the South, putting a serious dampener on hopes for state-level action there. The House cap-and-trade vote didn’t play a particularly big role in the election either way, but there’s certainly little good news for those hoping the U.S. might take the lead in this vital fight.

Climate hawks don’t have much to celebrate after the midterm elections, which saw the defeat of several clean-energy champions and the election of a wave of Republican flat-earthers. The Midwest is now almost as dominated by Republicans as the South, putting a serious dampener on hopes for state-level action there. The House cap-and-trade vote didn’t play a particularly big role in the election either way, but there’s certainly little good news for those hoping the U.S. might take the lead in this vital fight.

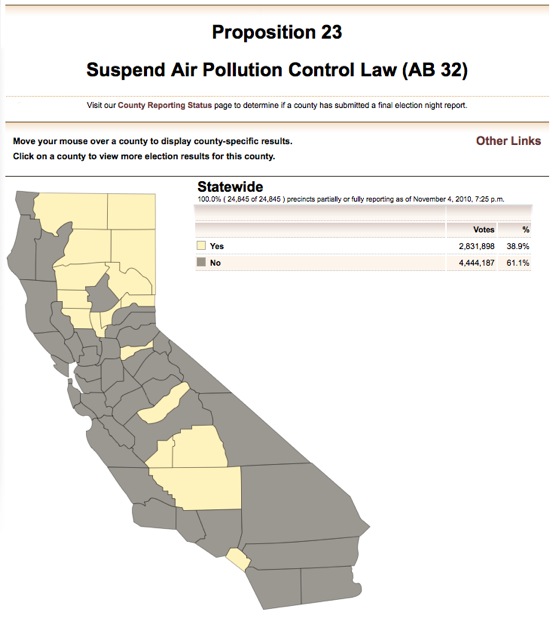

Except California! There climate hawks fought off Prop 23 and reelected two of their champions, Sen. Barbara Boxer and ’70s era governor Jerry Brown, who has a spectacularly ambitious clean energy agenda.

So why were climate hawks so successful in California while they’ve done so poorly at the national level? What lessons can be learned from the Prop 23 campaign? Folks on the ground in California will have a more detailed understanding than I do, and we’ll probably hear from some in coming days, but here are a few thoughts to get the discussion started:

1. A coalition that’s both broad and deep.

Green groups made much of the fact that the coalition pushing for a comprehensive climate bill at the national level contained all sorts of unexpected and non-traditional groups. Businesses! Religious groups! Military folk! And it’s true. A lot of work was done assembling that coalition. But as the events of the last two years demonstrate, while it was impressively broad, it was quite shallow, in two ways.

One, it was shallow in terms of depth in crucial swing states. Senators don’t care about broad coalitions, they care about interests in their states, and the green movement just didn’t have enough people on the ground in those states to make a ground-up fuss. And two, it was shallow in terms of intensity. Lots and lots of groups signed on to various statements and letters, but a relatively small subset really threw themselves into the work of lobbying and advocating.

The California coalition had depth in both those ways: It developed deep roots across the state, and the groups involved — social justice groups, cleantech groups, celebrities (which, remember, are a local constituency in California) — were really, really fired up.

2. Money.

Part of the problem with the national push is that fossil-fuel interests are still able to wildly outspend clean-energy forces, mainly because most of the latter’s money comes from environmental nonprofits. There’s no clean-energy industry big or robust enough to put serious money into a national contest. There were some big corporations on board, but none of them had an existential interest in the outcome the way both dirty and clean energy firms do and none came even close to countering fossil money.

In California, the clean energy industry is more than an idea, it’s a reality on the ground, and it includes some very rich and very influential people who are able to pay their way into the state capitol to make their case. Altogether the No on Prop 23 forces managed to outspend the giant oil companies funding the Yes side. Suffice to say, that rarely happens in clean-energy fights!

3. A compelling narrative with white hats and black hats

Part of the problem with the national climate bill was that the legislative strategy was focused on wooing evildoers. From the minute the bill got underway in the House, there was one bad visual after another of politicians and corporate lobbyists in back rooms making unsavory deals. That made it very, very difficult to frame it as a battle against a nefarious enemy. It just looked like business-as-usual in D.C. “The process” became the bad guy.

In California, two gigantic Texas oil companies did the No on 23 campaign a huge favor by showing up and playing the role of villain to a T. They dumped a huge amount of out-of-state money into the 23 campaign and instantly became visceral representatives of The Enemy: a bunch of rich fossil-fuel barons who want to tell California how to run its affairs. That’s beautiful: simple, compelling, emotional. It’s something that someone who knows nothing about climate change or policy can immediately grasp.

4. Experience on the ground

It’s somewhat harder to measure or quantify this one, but I think it’s a real factor. Unlike most of the rest of the country, California is not a noob when it comes to clean energy and efficiency. Californians are familiar with efficient appliances and solar panels on roofs, not in a novelty kind of way but in a workaday kind of way. They know people who work in cleantech and see that industry thriving when so many others are hurting. This stuff is part of their lives in a way it just isn’t for most Americans. Which suggests that creating real action on the ground, no matter how fragmented or insufficient, is a crucial step toward getting Something Big.

What do y’all think? Why did No on 23 succeed so wildly while the national effort flailed?

——

UPDATE: Earl Withycombe’s comment in the thread below (which I can’t link to because of Grist’s $*%! content management system) reminds me that I mean to add another to the list above.

5. Bipartisan (or at least unexpected) leadership

It really did matter that one of AB 32’s biggest backers is a Republican, Arnold Schwarzenegger. I don’t think we should fool ourselves by saying “this shows clean energy is a bipartisan issue.” One Republican zigging while the vast majority are zagging does not bipartisan make. But in terms of the heuristics the public applies to issues like this, it matters that there are leaders or prominent advocates that come from “the other side,” whatever the side may be (could be the military, business, farmers, whatever, anything traditionally seen as non-liberal). It’s an extremely efficacious bit of symbolism.