Zi Chua spent much of her summer vacation knocking on doors and asking New Yorkers to vote for candidates she believed would take the strongest action on climate change. When she wasn’t trying to get out the vote, she was busy holding elected officials accountable — as in early August, when she helped plan a morning sit-in at Andrew Cuomo’s New York City office.

Chua and other youth organizers hoped to pressure the New York State governor to disavow contributions to his gubernatorial re-election campaign from oil, gas, and coal interests. Cuomo had opted out of taking a pledge to refuse donations from the fossil fuel industry and its lobbyists.

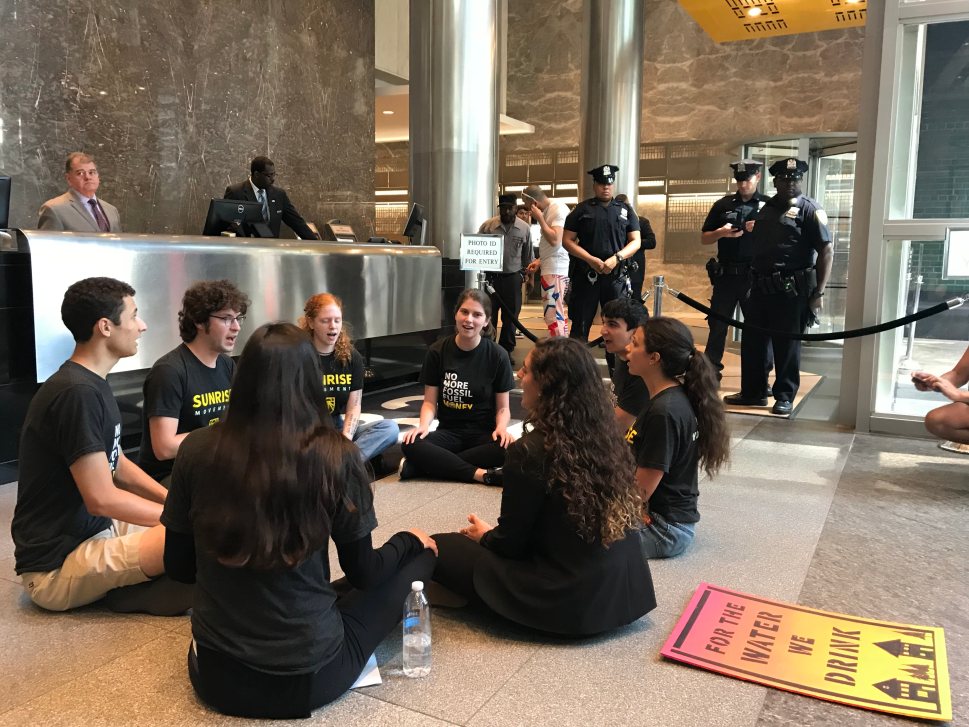

When police arrested eight demonstrators under the age of 25 at Cuomo’s Manhattan office, some wore T-shirts with the words “Who says youth don’t vote?” emblazoned on the back. It was a warning to politicians that the country’s youth are raising their voices.

In past elections, however, the youth turnout has been lackluster. In 2016, fewer than 40 percent of 18 and 19 year olds nationwide voted (according to data from from the youth civic engagement initiative, YVote). For comparison, 55 percent of all eligible voters cast ballots. In the 2014, midterms, just 14 percent of these young people made it to the polls — versus slightly more than 35 percent of the entire electorate, the lowest overall turnout since World War II.

Today, young people have the potential to wield increasingly significant electoral power. When the next presidential election comes around in 2020, millennials and members of following generation, Generation Z, are expected to make up 40 percent of the U.S. population. In just the next two years, 22 million potential voters will become eligible to cast a ballot.

Members of Sunrise Movement, a youth-led group dedicated to getting fossil fuel money out of politics, hold a sit-in at New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s Manhattan office. Justine Calma

Chua, who is 20, most likely won’t be one of those voters. The college sophomore grew up in the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur and moved to Boston to attend Wellesley College. But she’s among a growing youth movement that cares so much about the climate that it’s working to influence elections. And even if individual members can’t vote themselves, they want those who can to know how their actions will impact the world that youth will inherit.

Take 19-year-old Christian Acevedo, who was born and raised in Miami. He credits his increased passion to take on climate change this election season to Hurricane Maria, which ravaged his father’s native Puerto Rico almost exactly one year ago this month. He recently pledged to become a climate voter through an initiative led by Generation Progress, the youth-engagement effort of the progressive think tank Center for American Progress, and the climate-focused multimedia campaign The Years Project.

“It was like someone lit a fire under me, and I just really wanted to get out there and be engaged,” Acevedo said.

While a handful of young activists occupied the lobby of the skyscraper where Andrew Cuomo’s office is located, Zi Chua rallied dozens of others gathered outside. The youthful crowd carried signs that bore slogans like, “Lose our trust, lose our vote.”

The protesters had begun gathering at 10:30 that morning at the Midtown building. After an hour of chanting slogans like, “Whose side are you on?” Chua began to worry about the group’s ability to keep its energy up — especially with its peers risking being arrested inside.

A young activist is arrested and removed from Governor Cuomo’s New York City office during an August sit-in. Justine Calma

“I think everyone is getting tired,” she told me. “They need to keep it up because they’re still sitting in, and we need to support them.”

Fewer than 10 minutes later, police began arresting the activists inside as Chua and others encouraged the crowd outside to raise their voices. As the demonstration came to an end, those who organized the event invited participants to join them the following day to phone bank for Cuomo’s rival in the Democratic gubernatorial primary, Cynthia Nixon. (Six weeks later, Cuomo would fend off Nixon’s challenge.)

Chua and the demonstrators that August morning are members of the Sunrise Movement, a youth-led effort to organize against politicians backed by big oil in the hopes of electing leaders it believes will stand up for the planet and the people most impacted by climate change. (Sunrise’s co-founders Evan Weber and Varshini Prakash were Grist 50 honorees in 2017 and 2018, respectively.) Throughout the summer and fall, Sunrise placed 70 fellows from across the country in key voting districts in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Florida, New York, and Minnesota. During its “Sunrise Semester,” fellows have been charged with waging what the group calls a “massive youth intervention in the 2018 midterm elections.”

Sunrise isn’t the only youth-led group pushing for a green wave this election season. Rachel Lee is a 15-year-old high school sophomore from the New York City suburb of Closter, New Jersey. She heads up the New York chapter of Zero Hour. The group organized youth climate marches across the United States this summer, and Lee has been tasked with keeping the movement going through this upcoming school year.

Ahead of Jerry Brown’s Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco earlier this month, Lee schlepped into the city on a school night to help lead a march on climate intervention, green jobs, and bringing awareness to environmental injustice.

“With homework, project assignments, and stuff like that, it’s hard to find time,” Lee said, adding she had a history essay due at midnight. But she was more concerned about the future of the planet.

“Priorities,” she said jokingly. “If you’re passionate enough about climate change then you’ll do anything to come here.”

Nationwide, Zero Hour chapters are calling for the divestment of public and private funds from fossil fuels and big agriculture, a transition to 100 percent renewable energy 2040 (that doesn’t leave vulnerable communities behind), and a complete halt to the development of all new pipeline projects and oil and gas infrastructure. Lee and New York Zero Hour members are also hoping to pass the Climate and Community Protection Act, which would accelerate the state’s commitment to ditching dirty energy.

Sylvana Widman is another high schooler hoping young people can push that legislation through the New York State Assembly this winter. The 16-year-old is the chair of another student organization, the Youth Progressive Policy Group, which lobbies the state’s legislative body. Its primary focus is supporting a bill to lower the legal voting age to 17, and the group is already working on a voter registration drive and setting up booths in high schools to get young voters engaged.

Thanks largely to Widman’s leadership, the group also decided to take on environmental issues. It’s gearing up to fight for the Climate and Community Protection Act this winter. When it comes to balancing high school and changing the world one election at a time, Widman told Grist, “It’s kind of overwhelming but, you know, climate justice doesn’t stop for anyone.”

That sense of working towards something bigger than themselves is what weaves each young leader’s actions into a movement that legislators will have to reckon with this fall. It’s what motivated Chua with Sunrise Semester to spend three hours each day attempting to reach up to 100 voters in roughly 70 homes within her assigned “turf.”

Zi Chua (center) and other members of Sunrise Movement rally protesters outside Andrew Cuomo’s office in August. Justine Calma

It’s not glamorous work. Sometimes she had doors slammed in her face. “You woke me up for this?” she recalls one resident telling her.

But she was determined to get voters thinking about the impact they can have on the planet where we all live.

That’s why she feels she has a stake in this election, too. As the the second-biggest carbon emitter, the U.S. is currently behind only China in contributing toward our warming climate. And the rising global temperatures that Americans are helping to fuel are threatening access to food and clean water in Chua’s home country of Malaysia.

“Their individual decisions as voters affect the rest of the world,” Chua said. “I’m part of the rest of the world.”