This story was originally published by CityLab and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

For an idea of what President-elect Donald Trump thinks about environmental justice — that is, when minorities and low-income communities suffer disproportionately from environmental harms — look to the Bronx.

There, one of Trump’s companies is running a golf course built over a landfill, right next to a public housing development. When the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance first learned of the golf course plans — announced by then-mayor Rudolph Giuliani back in 1998 — the group warned that construction on this site would apply downward pressure on the landfill’s decomposing waste, releasing toxic gases into the groundwater and the basements of the homes nearby. The alliance sued to stop the project but failed.

Sure enough, reports of exceedingly high levels of methane gas were recorded in the homes near the golf course site in 2012. Amid costs overruns galore, Trump’s company had won a bid to operate the golf course the year before. The Trump Golf Links at Ferry Point opened for business in April of 2015, despite the risks it poses for residents who live near it. Trump’s company now wants to expand the golf course, over the Bronx community’s wishes, and with an admission price that’s well above what this district — one of the poorest in the nation — can afford.

If the case of the gassy golf course offers any hint of how a President Trump might pursue his agenda over the concerns of affected citizens, it spells big trouble for federal environmental justice policy, which is one of the few policies that requires the government to consider the impacts on communities of color and low-income before allowing development.

“The things we’ve been advancing, in terms of race and class analytical frameworks and dealing with the compounding structural problems that disproportionately affect our communities — that all feels like a luxury now,” says Eddie Bautista, executive director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance.

Bautista’s been in countless meetings over the past month packed with frantic environmental and climate justice activists hunkering down around what they’re calling “resistance planning.” The main concern: How will they get the federal government to pay attention to the families living on the frontlines and fencelines of environmental hazards moving forward?

Most environmental justice work is done locally, as is much climate justice organizing, working to build neighborhood resiliency for when climate disasters strike. But as Bautista says, a lot of that local climate adaptation and brownfields cleanup work can’t be done without the help of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which supplies them with grants and technical support.

Trump’s pick to head the EPA, Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt, appears unlikely to be an ally: In fact, he’s been embroiled in litigation against the EPA, fighting to make it less burdensome for companies to pollute. Climate justice? Pruitt questions whether climate change is even a thing. “Forget EPA,” says Bautista. “We may have to change the name to PPA, the Polluter Protection Agency.”

It’s not just at the EPA where environmental justice work is threatened. Department of Energy nominee Rick Perry fought against voting rights his entire career as Texas’s governor, and calls climate change a “contrived, phony mess.” Perry’s disdain for both issues is perhaps only outdone by Jeff Sessions, Trump’s choice for attorney general. Montana Rep. Ryan Zinke and ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson, Trump’s picks for Interior and the State Department, respectively, both have close ties to the oil industry, whose pollution and climate impacts fall most devastatingly on people of color. And even Trump’s African-American pick to lead the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Ben Carson, has disavowed the work the Obama administration has been doing to undo segregation.

Collectively, this group embodies the kind of business-casual racism that has led to federal policies that have created racial inequities across the board — housing, health care, law enforcement, transit design, parks, infrastructure. And they are now poised to reverse the considerable progress that’s been made in addressing those disparities.

The EPA, in particular, has covered a lot of ground over the last eight years in rooting out the racism often found in environmental policy. The agency’s recently released EJ 2020 Action Agenda is a roadmap for future EPA staffers to follow for protecting the lives of low-income and minority populations in its operations.

But, if Trump covers any ground with the EPA, it likely will be with an action agenda that — like his Bronx golf course — is more interested in the lives of the white and wealthy. This could mean the end of environmental justice at the federal level as we know it.

From Nixon to Bush, a movement emerges

Before measuring the damage that Trump might do to environmental justice, it’s critical to understand how a science-based agency ended up with a class-and-race-based mission to begin with.

When the agency was created in 1970 — proposed and established by President Richard Nixon — there was nothing in its charter about racial discrimination; it wasn’t the agency’s business to examine why toxic landfills were next to public housing projects, or more often placed near poor, black communities than white ones.

But black activists, many of them veterans of the civil rights movement, were determined to change this dynamic. They banded with a burgeoning band of black public health professionals and scientists throughout the 1970s and 1980s to draw attention to the environmentally unsafe living conditions of poor people and people of color. It was a movement with no name, but its influence would be felt widely. It attracted one young black man in the late 1980s to the South Side Chicago projects, where resident-activists had been clamoring for the housing authority to remove asbestos from their dwellings for over a decade.

That young man would later become the first black President of the United States, but the newly named environmental justice (or “EJ”) movement got into the White House well before him. After a series of summits and protests on the front steps of the U.S. Capitol Building in the early 1990s, EJ activists were invited to witness President Bill Clinton sign executive order 12898 on Feb. 11, 1994, which begins:

To the greatest extent practicable and permitted by law, and consistent with the principles set forth in the report on the National Performance Review, each Federal agency shall make achieving environmental justice part of its mission by identifying and addressing, as appropriate, disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of its programs, policies, and activities on minority populations and low-income populations in the United States and its territories and possessions, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the Commonwealth of the Mariana Islands …

And with that, environmental justice officially became the federal government’s business. The order applied to all cabinet-level departments, with the EPA as the lead agency. EPA scientists were expected to weave civil rights statutes into their planning and assessments, but it was handed this mandate with virtually no guidance and little funding to execute it. Clinton left the EJ order vulnerable to manipulation, which is exactly what George W. Bush did when he became president in 2001.

“EJ activities had already begun to lose steam in Clinton’s second term,” says David Konisky, author of the 2015 book Failed Promises: Evaluating the Federal Government’s Response to Environmental Justice. “When the Bush administration came in, not only was it not a priority, but EPA Administrator [Christine Todd] Whitman put out a memo that in essence signaled to the agency that they were going to issue a new understanding of environmental justice that would reduce the emphasis on poor, minority communities and instead saying that it means environmental protection for everybody.”

In other words, EJ got All Lives Matter-ed. This became a hallmark of the Bush doctrine, with his administration even going so far as to suggest that any policy that helped historically harmed populations was discriminatory towards whites. Al Huang, an environmental justice lawyer for the Natural Resources Defense Council, remembers other ways Bush attempted to undermine the EJ agenda, which could offer a glimpse of what’s in store now.

“We saw during [the Bush administration] increased secrecy and lack of transparency by federal agencies,” says Huang. “The Freedom of Information Act is the key to lifting the veil on the interference of corporate polluters in policy making, and Trump is angling to appoint people with corporate polluter backgrounds.”

With no federal assistance, the duty of funding ways to protect historically disadvantaged and pollution-overburdened communities was shifted to foundations and nonprofits. In some ways, this was better for EJ communities. The foundations could commit more resources than the EPA was willing to, and they had passionate staff members from some of the most deeply affected neighborhoods. The philanthropic sector funded grassroots organizations to carry out tasks like brownfield cleanups and backyard air and water monitoring.

Some states took up the mantle as well. Michelle DePass, an African-American woman who once served as the environmental compliance manager for San Jose, California, was instrumental in developing EJ policy at both the philanthropic and state government levels during the Bush years. While serving as senior policy advisor for New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection in the early 2000s, she helped draft the state’s environmental justice administrative order, which New Mexico quickly adapted. She went on to become a program officer for the Ford Foundation, where she produced an environmental justice grant portfolio that helped take the movement global. [Editor’s note: Michelle DePass is a member of Grist’s board of directors.]

“We don’t just work on EJ because we want to, it’s because we have science and evidence that shows us the impact on these communities,” says DePass, who currently serves as dean of The New School’s Milano School of International Affairs, Management, and Urban Planning. “Foundations and nonprofits began pushing the understanding of regulatory process and a roster of community-based organizations around the country started to focus their efforts on the states because it was obvious that the federal government was not providing support or scientific research or enforcement. The EJ organizations did not want to lose all of the gains they had made from the previous administration.”

“Give an EJ group $25,000, they’ll do what a city will do with $2 million.”

The movement made big strides in the first half of the 2000s, especially in cities throughout New York, New Jersey, Michigan, Texas, and California. EJ activists launched investigations into the siting of toxic waste facilities, poor pollution controls on fossil fuel–burning power plants, and the spraying of pesticides near poor, black, and Latino neighborhoods and Native American tribal homes.

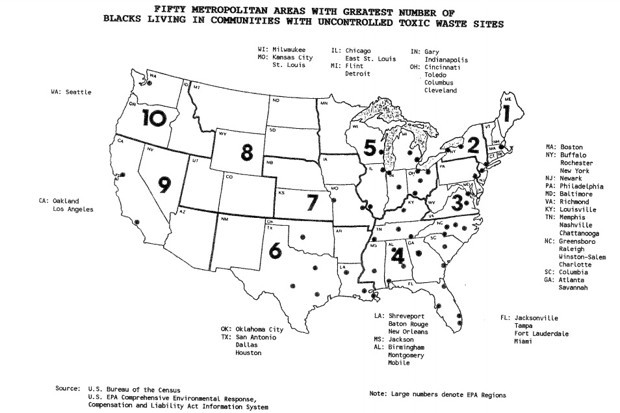

An emerging class of attorneys with backgrounds in environmental and civil rights law used this research to bring lawsuits on behalf of overburdened communities. The New York City Environmental Justice Alliance’s 2000 lawsuit against Trump over his golf course plans is one example of this. That lawsuit failed, however, as did many other EJ cases, because of weak enforcement of anti-discrimination laws and court rulings that were growing increasingly hostile to environmental discrimination claims. In 1987, a landmark report found that African Americans were far more likely to live near a toxic waste site than whites, and a follow-up report published 20 years later found that nothing had changed.

The United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice

It could have been worse — Bush could have simply rescinded executive order 12898. But he didn’t, and it lived to see another day under a very different administration: In 2008, a president who was schooled by a bunch of environmental justice activists in Chicago arrived in the Oval Office. Obama wasted little time resurrecting the EJ agenda, which was a core priority even for his transition team before taking office.

“[Environmental justice] was acknowledged, people understood what it was, and the president made every effort to ensure that there were people on the transition team who could easily jump in and understand what was going on,” says DePass, who served on that transition team. “We pulled together a very large EJ gathering at the White House, inviting EJ leaders from around the country to dialogue about these issues. We wanted to hear from people directly to gather their thoughts on what the EPA has or hasn’t been doing, what they thought it should be doing, and the impacts that have occurred in their communities.”

Obama’s pick to lead the EPA, Lisa Jackson, who previously had worked with DePass at New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection, made EJ one of her top priorities. What that meant was having her staff immediately get to work on creating a manual for how to infuse environmental justice considerations into the agency’s strategic planning and decisions.

The culmination of that work was a set of guidelines the agency released in 2014 (called Plan EJ 2014) so that no future EPA staffer could ever again say that they didn’t know what EJ means or how to make it part of their work. The plan explains how to weave EJ into the agency’s rule-making, permitting decisions, and enforcement actions, and how to create partnerships between federal officials and city and tribal governments. That plan was upgraded this year to what’s now called EJ 2020, an action plan with more specific steps on how to carry this mission out, especially at the local level.

It took all eight years of the Obama administration for the agency to reach this level of tangible EJ engagement — 20-plus years if you start the clock at the signing of the executive order that made it possible. All of this progress could be undone within the first 100 days of Trump assuming office.

At best, Pruitt (if confirmed) could simply put the EJ agenda on ice, as Bush did. At worst, Trump could rescind the executive order and wipe out everything that comes along with it. For Lisa Garcia, who was instrumental in creating the EPA’s EJ plans when she worked there from 2009 to 2014, that would be a “horrific” outcome.

“Some of our biggest successes were the grants we gave that go directly to communities to clean areas up, and build health clinics, and even leadership and capacity building,” says Garcia, who’s now an attorney for Earthjustice. “That’s our urban waters grants, our sustainability grants — if they get rid of all of those, that’s a direct hit to the communities that don’t have a lot of resources but that do wonderful work. The joke is, if you give an EJ group $25,000, they’ll do what a big city will do with $2 million.”

The timing for such undoing would be unfortunate considering recent high-profile EJ scandals. The Flint water crisis and the Standing Rock standoff are both evidence of a public that is increasingly more “woke” about the justice implications of environmental policies, and the Keystone XL pipeline controversy and Hurricane Sandy have further charged the climate change conversation with the language of justice.

The EPA’s EJ plans are the only official documents that encode justice terminology into environmental policy. And those plans are supremely vulnerable for erasure.

“There are no environmental justice regulations for EPA,” says DePass, who served as assistant administrator for the EPA’s Office of International and Tribal Affairs during part of the Obama administration. “There’s EJ Plan 2014 and EJ 2020, and within those plans are the best practices for dealing with what the science is showing, which is that we still have communities that are not being protected. There were efforts made throughout the agency to respond to the information that we had, but it wasn’t put into regulations because we felt it didn’t need to be. There was not a political appetite for new regulations. We did what we could.”

It’s also important to note that the EPA’s enforcement of civil rights and anti-discrimination policies, codified or not, have never been stellar, even under the friendly Obama administration. In September, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights issued a 230-page report berating the EPA for its poor record on this front. Among its many findings:

- Racial minorities and low-income communities are disproportionately affected by the siting of waste disposal facilities and often lack political and financial clout to properly bargain with polluters when fighting a decision or seeking redress.

- The EPA has a history of being unable to meet its regulatory deadlines and experiences extreme delays in responding to [Civil Rights Act] complaints in the area of environmental justice.

- The EPA’s Office of Civil Rights has never made a formal finding of discrimination and has never denied or withdrawn financial assistance from a recipient in its entire history, and has no mandate to demand accountability within the EPA.

To be fair, the EPA has cleared much of its civil rights investigation backlog up over the past few years, and the EJ 2020 plan is supposed to ramp up enforcement activities considerably. But that plan was only finalized in the last few months, meaning it hasn’t really had a chance yet to do what it is designed to do. If Trump takes away the agency’s EJ resources, he could cause the EPA to skank this shot at racial redemption just as the agency is teeing up.

“A fast track to the emergency room”

Robert Bullard, who is considered the “father of environmental justice,” stepped down from his job as dean at Texas Southern University in August this year to throw himself full-time into an activist campaign to draw more attention and resources to the Southern states. This is the region where minority and low-income populations are most heavily concentrated, and it’s also where a medley of extreme weather events — hurricanes, floods, and wildfires — have proliferated. Bullard says the prospect of Trump potentially destroying decades of federal EJ work only makes his campaign more necessary.

“When you hear Trump appointees saying they want to dismantle and fast-track environmental regulations, we think that’s just a fast track to the emergency room, in terms of people getting sick from the pollution that results from that,” says Bullard. “There will come a point when even the most ardent supporter of Trump will say this is not acceptable, to allow communities to be poisoned like this.”

Even if this is indeed the end of environmental justice at the federal level, it’s not the end of the movement, which is already evolving into the climate justice movement, expanding its reach and numbers. The real justice work is ground out at the grassroots, and the movement’s progenitors have not forgotten this. There’s otherwise little room for optimism here, but EJ advocates remain hopeful.

“I’ve heard that people at the agency are ready to stand tall and say that this is a bipartisan issue, because who doesn’t want low-income communities to be healthy communities?” says Garcia. “Trump will have to pick his battles, and if he’s going to focus on things like a border wall then maybe the EJ work will remain. If they’re focused on jobs maybe they can even turn it into great training opportunities, for cleaning up Superfund sites or installing new technology. They’ll need to work in those low-income communities to bring those jobs home, and maybe make sure they’re healthy while they’re at it.”

Hopefully that golf course in the Bronx is hiring.