Which phrase does a better job of grabbing people’s attention: “global warming” or “climate change”? According to recent neuroscience research, the answer is neither.

If you want to get people to care, try “climate crisis,” suggests new research from an advertising consulting agency in New York. That phrase got a 60 percent greater emotional response from listeners than our old pal climate change. (It must be music to the ears of Al Gore, who uses the phrase in just about every other tweet.)

SPARK Neuro measures brain activity and sweaty palms to gauge people’s emotional reactions and attention to stimuli. The company is backed by a wildly diverse range of investors, including Peter Thiel, founder of PayPal and famous libertarian, and Will Smith, Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. Netflix, NBC, and Paramount have used its services to gauge interest in ads and movie trailers. And now SPARK Neuro is turning its attention to climate change.

For the experiment this spring, SPARK Neuro brought in 120 people — divided evenly among Republicans, Democrats, and Independents — and sat them down at the lab. Participants wore electroencephalography (EEG) devices on their heads so the researchers could measure the electrical activity coming from their brains every fraction of a second.

While a webcam tracked their facial expressions, little straps on their fingers measured the sweat that accompanies heightened emotions through galvanic skin response — the main technology that’s used in lie detector tests. SPARK Neuro takes the tornado of data from all of those sources and runs it through algorithms to quantify their subjects’ reactions to whatever they heard.

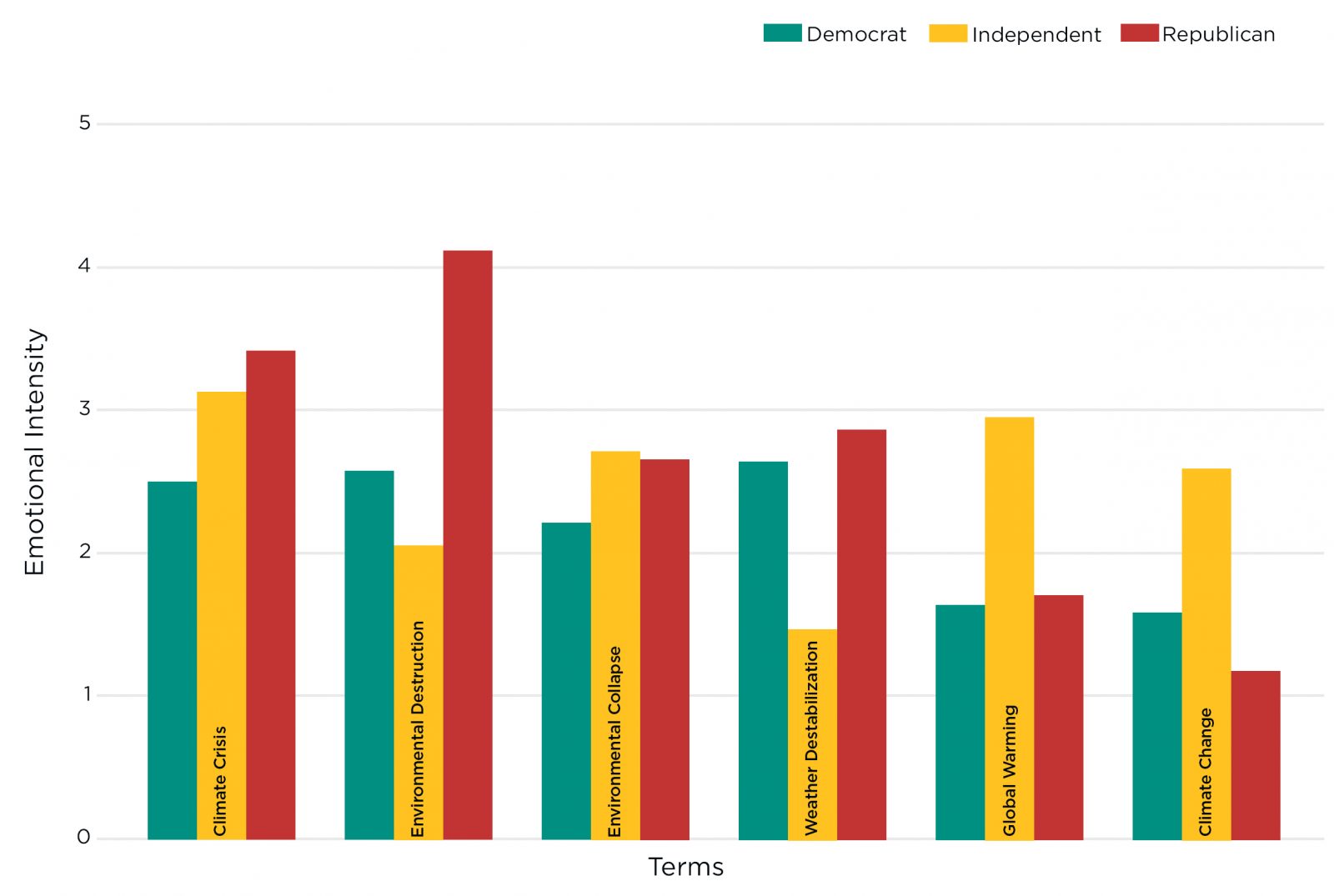

In this case, they listened to audio recordings of six particular phrases. “Global warming” and “climate change” performed the worst of all in terms of emotional engagement and audience attention. They were trumped by a batch of less familiar phrases: climate crisis, environmental destruction, weather destabilization, and environmental collapse.

SPARK Neuro

It’s the latest sign that climate change communicators have a whole lot to learn from cognitive science. “People understand that something is not working about climate change and that some change needs to be made,” said Spencer Gerrol, SPARK Neuro’s CEO.

It’s been an open secret that “global warming” and “climate change” might not be the best phrases to get the public engaged. Most people, after all, think that warm weather sounds pretty nice. And “climate change” naturally lends itself to confusion; after all, deniers say, hasn’t the climate always been changing? (It has, but nowhere near this dramatically!)

Gerrol came up with the idea to run a messaging experiment about how to frame the subject while talking to a colleague about the importance of language and how the right phrase can change policy. He pointed to the “estate tax,” which normal people didn’t care much about until Republicans started rebranding it as the “death tax” in the 1990s. Frank Luntz, a well-known messaging consultant for Republicans, further popularized the phrase in the early 2000s.

“As soon as they started calling it the death tax, people started caring,” Gerrol said. “Regardless of how you feel about the estate tax, that language changed people’s emotional perceptions, and ultimately that changed behavior and policy.” Since 2001, Congress has weakened the federal estate tax, temporarily repealing it in 2010. It returned in a weakened state in 2011 and took another blow under the 2017 tax bill.

Gerrol suspects that there are two reasons “global warming” and “climate change” performed so poorly. For one, they’re both neutral phrases. “There’s nothing inherently negative or positive” about the words themselves, Gerrol points out. (Luntz, as it happens, once encouraged Republicans to use the benign-sounding “climate change.”)

Then there’s the problem of overexposure. Both global warming and climate change are “incredibly worn out,” he said. There’s a reason why advertising companies aren’t using their ad campaigns from the 1980s — sometimes you need to shake things up to get people to pay attention. If a term doesn’t evoke a strong emotional response in the first place, it’s even more likely to wear out quickly, Gerrol said.

People who care about our warming planet are starting to realize the power of words. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s “Green New Deal,” for example, has helped push the conversation around climate policy into the mainstream. And George Monbiot, a Guardian columnist, has argued for replacing “cold and alienating” environmental terms like “nature reserves” with warmer and poetic phrases — say, “places of natural wonder.”

There’s no shortage of alternatives. Climate scientist Peter Kalmus recommends “climate breakdown.” The New York Times recently used “climate chaos.” Some scientists suggest “global heating.” But to know what really resonates, you have to study the brain.

Before the emerging field of neuroscience-based analytics, researchers relied on focus groups and surveys to learn how people felt. But those self-reporting methods are subject to a lot of biases that can distort results. People play for the audience. “You want to seem smart, seem caring, and you want to get the right answers,” Gerrol said.

Unlike those more traditional approaches, SPARK Neuro scans your brain activity and parts of your nervous system — because physiological activity doesn’t fib. The company’s work has been called a “lie detector on steroids.”

For the messaging experiment, participants were first shown neutral stimuli to establish a baseline. Then, they listened to recordings of the six phrases played at random. The phrases were either in isolation or in a sentence.

In both cases, the results were consistent, Gerrol said. The two phrases that caused the strongest emotional reaction overall were “climate crisis” and “environmental destruction.”

But a strong emotional response isn’t always a good thing, especially when it comes to a polarized subject like climate change. “Environmental destruction” actually evoked too much emotion from Republicans: a 55 percent stronger reaction than that group’s average response for all terms. That spike in emotion would likely have a “backfiring effect,” Gerrol said. They’d get so riled up that they’d likely experience cognitive dissonance — that uncomfortable feeling when something you learn conflicts with your values — and come up with counterarguments to get out of that mental pain.

“Climate crisis,” on the other hand, was the Goldilocks of the study — not too weak, not too strong. Among Democrats, Republicans, and independents, it caused a strong emotional reaction without going overboard. That kind of response leads people to pay more attention and encourages a sense of urgency, Gerrol said.

And that urgency is key. Much like retirement planning, another messaging problem SPARK Neuro is tackling, climate change requires planning for the future — not exactly a strength for the human brain. Present bias (valuing today more than tomorrow) is just one of many cognitive biases that inhibit us from taking climate change head-on.

To be sure, this initial research only looked into six terms, so there’s a lot more testing to do before settling on “climate crisis.” How would “climate chaos,” “climate breakdown,” or “global heating” measure up?

Maybe one of these phrases would do a better job of helping people realize that all those bad things they’ve been warned about are no longer off in the distant future. That scary future has already arrived.