The latest Gallup poll on American priorities, released this week, shows that Americans are far more worried about race relations than they were just a year ago. In 2014, only 17 percent of Americans said they cared a “great deal” about race relations. This year, that number jumped to 28 percent. The only issue that stoked a higher increase in concern from last year is the possibility of a “terrorist attack,” a vaguely defined category that we can only presume means an attack from a Middle Eastern country.

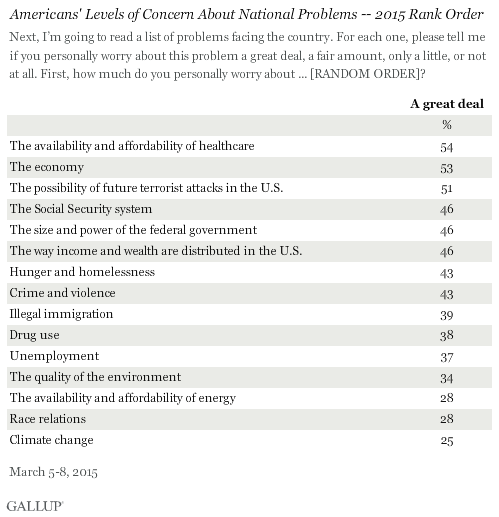

The jump elevates race relations above national concerns around climate change. But race and climate are in a race for last place on the list of national problems provided by Gallup:

I know, I once (or twice) said polls don’t matter, but this one deserves examination, to figure out why the terrors we see (racism, climate change) don’t stoke the same fear as terror unseen, at least on our shores. It also might be instructive for racial justice and climate justice movements seeking to register higher on the nation’s list of priorities. A few thoughts:

1. Terror by any other name is still terror.

In its blog, Gallup explains the concerns around race as a separate matter from “terrorist attack” anxieties:

Terror attacks in Paris and the rise of ISIS have formed the backdrop to a significant increase in concerns about such attacks taking place on American soil. At home, the racially charged incidents in Ferguson and elsewhere have amped up conversations on racism and police brutality, often creating a wedge within communities.

But for many African Americans, Gallup is, as Henry David Thoreau once said, “making a distinction without a difference.” What happened in Ferguson and “elsewhere” to black people are terrorist attacks, even or especially when the police are involved, as reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones recently wrote about in Politico.

Many believe the police are doing what they’re supposed to do, even in Ferguson. Still, the Department of Justice’s recent investigation into Ferguson’s police department concluded emphatically that the culture of policing there must radically change. The report basically found that Ferguson has been financing itself on taxing people for being black — arresting and fining African Americans to death for petty crimes like walking in the road.

2. Young black men are suffering.

Five days before the American priorities poll, Gallup released a report that showed African-American men aged 18 to 34 have a “statistically significant” lower Well-Being Index score than non-black men of the same age. This index measures financial and physical well-being, as well as levels of support from friends and family, and how one feels about “community pride, involvement, and safety and security.” Black men also more frequently report dismal outlooks on their own lives than non-black men, according to Gallup surveys.

We also are getting these reports in the same week that Kendrick Lamar released his highly anticipated sophomore musical effort “To Pimp a Butterfly,” an album flush with songs that aggressively wrestle with “well-being” — both black men’s and his own. His song “i” includes a repeating, self-affirming chorus of “I love myself,” while the corresponding “u” is a teardrop-soaked letter to himself about how much of a disappointment he often feels he is to his friends, family, and community.

3. Black lives matter — but where does the climate fit in?

The sharp rise in race relations concerns are likely linked to the confrontational, direct actions that people have been taking in response to the police killings of black men in Ferguson, Cleveland, New York City, and beyond. Meanwhile, we also had the largest climate change demonstration in history, but concerns around this issue have barely elevated since last year, and it falls dead last as a national concern. That might tell us something about tactics around raising awareness and fighting power.

The #blacklivesmatter movement has metastasized everywhere from the nation’s highways to Americans’ favorite brunch spots. I’ve questioned whether the brunch protests are effective ways to get more people to sympathize, or more importantly, join the #blacklivesmatter movement. But perhaps these chronic disruptions have been more impressionable than I’ve thought.

The People’s Climate March didn’t have the level of civil disobedience as the Ferguson demonstrations and their kindred rallies around the country. There has been follow-up PCM action, but again, in much calmer settings.

I’m not saying that climate hawks need to launch Seattle Battles around the country. The #blacklivesmatter rallies have been, for the most part, nonviolent, acknowledging the inexcusable recent Ferguson police killings, (whether directly connected to Ferguson protests or not). #Blacklivesmatter’s real targets are people’s consciences, not people and property. But climate activists could learn from these pressure tactics.

4. We’re fighting for the same cause.

The sharpest increase in American concerns since last year is about whether the nation suffers a terrorist attack. Meanwhile, there have been far more major hurricanes, drought, and displacement than violent attacks from foreigners in the years since 9/11. There have been far more police shootings and killings of black men than “terrorist attacks on the U.S.” These are the areas projecting the most suffering, and yet are registering the least concern among Americans.

Which means that the climate change and #blacklivesmatter movements really need each other right now. In many cities, African Americans get the double-terrorizing of being among the most vulnerable to climate change and police brutality. The climate movement has plenty to offer for black lives, in terms of jobs and resources and security. I’m betting the benefits would be mutual.

Meanwhile, Americans need to answer for themselves why they are more perturbed with unrealized terrorist attacks from people overseas, while blinding themselves to the real-life terror happening before our very eyes.