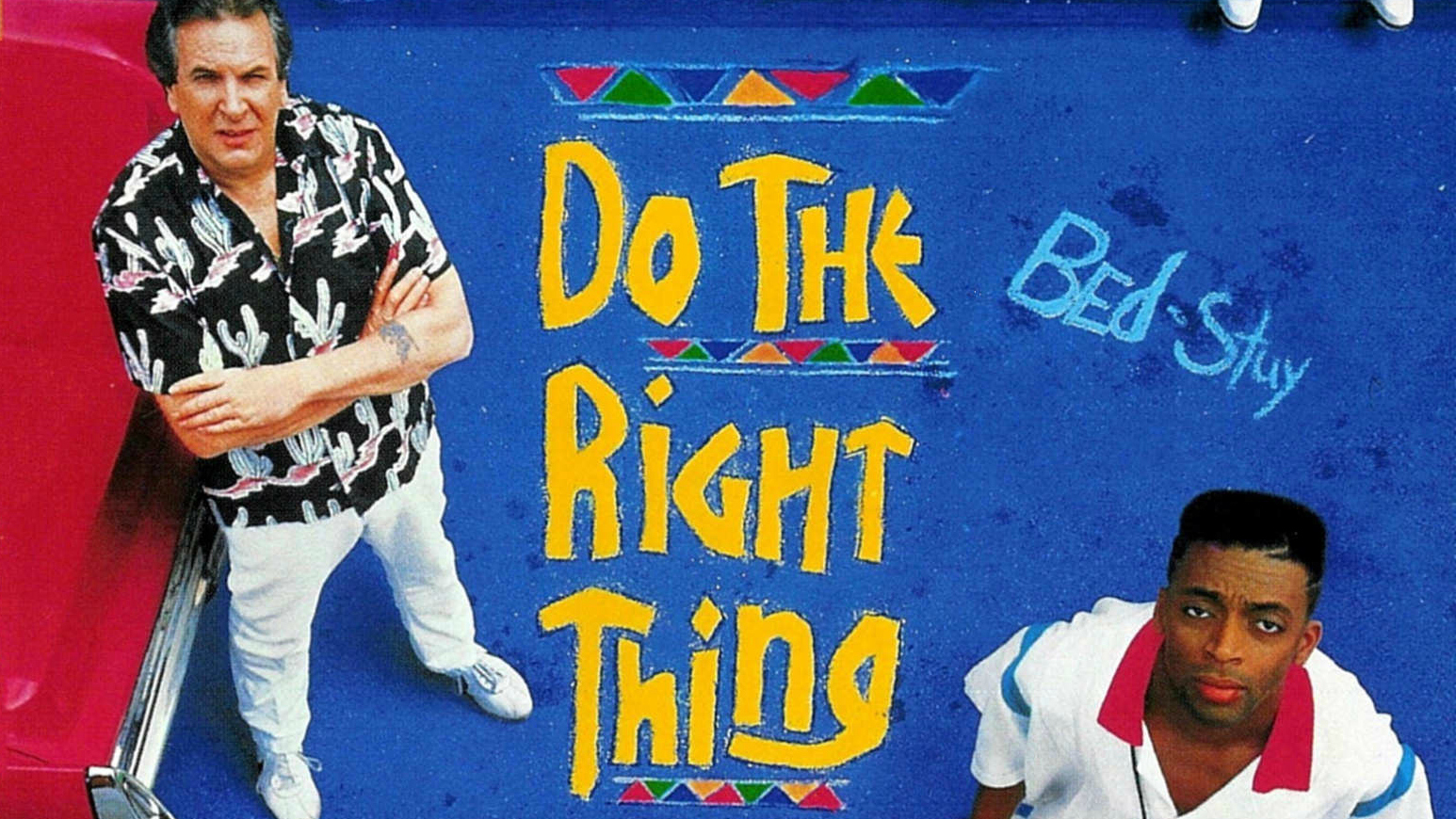

Today marks the 25th anniversary of Spike Lee’s film Do the Right Thing, listed by the late, great critic Roger Ebert as one of America’s greatest movies. It wasn’t Lee’s first film, but it was the one that launched him into legendary cinematic status and comparisons to other lauded New York filmmakers like Woody Allen and Martin Scorsese. In celebration of the anniversary, Lee held a block party over the weekend on the Bed-Stuy block where the movie was filmed, with performances from Public Enemy, Erykah Badu, and Dave Chappelle. The First Family even streamed a video message to the party, noting that Do the Right Thing was the movie Barack and Michelle saw on their first date.

While “Do the Right Thing” is best known for its commentary on race relations, there are some prophetic moments and prognostic themes in the film for those concerned about climate change and cities.

1. The heat is on

The temperature is set in the first few scenes of the movie: It’s freakin’ hot. Radio DJ Love Daddy (Samuel Jackson) warns people with Jheri curls that the heat might melt their hairstyles into plastic helmets. Da Mayor, played by the late Ossie Davis, wakes up in what looks like a hellhole, shirtless and sweating profusely, his old age signalling that he might not hold up under the sun. Italian pizzeria owner Sal (Danny Aiello) pulls up to his shop with his two sons immediately bomoaning the humidity. His son Pino (John Turturro) complains that the maintenance guy still hasn’t come to fix the air conditioner. Sal responds that maintenance won’t come to this Bed-Stuy neighborhood in Brooklyn without a police escort. Motha Sista, played by the recently deceased Ruby Dee (Ossie Davis’ wife at the time), warns Spike Lee’s character, Mookie, not to work too hard or he “might fall out from all this heat.”

Bed-Stuy is an urban heat island, one of the most lethal killers under climate change, as the recent U.S. National Climate Assessment points out. When this movie debuted, we were experiencing inexplicably hot summers. At the time, NASA found that the three hottest years in its 134 years of tracking were during the decade of the 1980s. This was, of course, later eclipsed by the 21st century’s hottest years of all-(recorded)-time. Do the Right Thing was filmed after the deadly North American drought of 1988, which, combined with intense heat waves, led to upwards of 10,000 deaths.

When we think of heat-related deaths, we envision elderly people with heart problems who can’t manage under extreme temperatures. But Lee’s film also shows how heat exacerbates underlying tensions and anxieties in our communities, especially those where racial, cultural, and class differences are apparent. Broken air conditioners don’t get fixed because the maintenance guy won’t come into a black neighborhood. Labor is affected. Motha Sista wants Mookie, Sal’s pizza delivery guy, to take it easy. But when he takes work breaks, Sal chastises him for being “lazy.” And when Mookie takes a shower break at home, his sister scorns him some more for being irresponsible with his job. Do the Right Thing’s suspense builds as the temperature rises. The destruction at the movie’s conclusion is an apt metaphor for what will happen as the Earth’s temperature rises under climate change, enflaming communities’ socioeconomic problems in the process.

2. The first movie to bring melting polar caps to our attention

Before EPA and scientists began tying climate change to urban heat islands and asthma, the impacts most associated with global warming were melting polar caps and sea-level rise. Do the Right Thing made direct mention of this long before Al Gore’s Inconvenient Truth brought it to the big screen. When we first meet the neighborhood jesters ML, Sweet Dick Willie (Robin Harris R.I.P.), and Coconut Sid, global warming is one of the first topics at hand.

“Well, gentlemen, the way I see it, if this hot weather continues, it’s going to melt the polar caps and the whole wide world,” ML tells his friends, “and all those parts that ain’t already water will surely be flattened.”

His partners laugh him off, but ML is unbothered. When the world starts drowning, ML will float off on a boat. “And I ain’t gonna drop you no rope, no life preserver, no nothing,” he tells the crew. This only invites more ridicule from them. “How you gonna buy a boat?,” asks Sweet Dick Willie. “You 30 cents away from a quarter.” ML displays his solution: a lottery ticket.

ML might not be a “climate hawk.” He’s definitely no millionaire who can afford to adapt when the worst of climate change comes. His position — trapped in an overheated, concrete jungle — makes it more likely that he’ll be a victim rather than a survivor. Sixteen years later, on another urban heat island hundreds of miles south of Brooklyn, Katrina happened. We saw many people like this movie’s characters who were left stranded in the waters — no boat, no car, no lottery-ticket luck. Just death. When I first saw this scene in Do the Right Thing, as a 12-year-old, I had no context for what these men were talking about. I joined Sweet Dick Willie and Coconut Sid in laughing at ML. Today, I know this ain’t no joke.

3. Whose water is it?

One of the most fragile of our natural resources under climate change’s worst scenarios is water, and not just for the reasons ML references. When the heat gets turned up, the freest, most plentiful solution is cold water. In one scene, the neighborhood teens pry the lid off a fire hydrant and use cans to spray the other kids and anyone in the vicinity. It’s done in fun, but also to cool everyone down on the scorching hot day. When the driver of a convertible gets drenched while driving by, he summons the police, who close up the hydrant and end the festivities, disappointing the neighborhood kids. “You wanna get wet, go to Coney Island,” says one officer. But as I’ve written about here, here, and here, many black kids have been shunned or excluded from pools and beaches — Coney Island in particular, even today — which is why many don’t swim. Spraying from the fire hydrant has been a favorite pastime of many black youth since as long as I can remember.

Problem is, the city controls the hydrants, and super-soaking is not an authorized use of the equipment. It’s for putting out fires. At the movie’s conclusion, though, the fire department weaponizes the hydrant to spray at black and brown folk when they respond angrily to the police for killing the community giant Radio Raheem. These kinds of tensions over who can use water and for what reason will flare up even worse as water becomes a scarcer resource in a climate-changed world.

I want to be clear: This movie was not about global warming. It was a movie about the unresolved problems in our cities and communities — racism, classism, sexism, police brutality — and what happens when you apply heat and pressure. Since the film was released 25 years ago, our summers have only gotten hotter. Back then, we did not have the climate change facts and vocab we have today. Now that we have them, it only makes sense to do what the movie’s title tells us.