Oil is cheap! Crude prices around the world have fallen under $50 per barrel for the first time since the 2009 financial crisis. That’s because supply is up. The U.S. and Canada are tearing up the earth to wring out more tar sands and shale oil, while recent conflicts in other key oil-producing nations have settled down and led to a big surplus. The early results: Gasoline is dirt-cheap, SUVs are making a comeback, and airlines are making bank.

For the climate, the price drop might seem like an obvious nightmare. Cheaper gas means more gas guzzled and more carbon emitted, right? The reality is actually more nuanced.

Lately, much has been said, written, and prognosticated about the ripple effects of cheap oil. Here, we present the potential bad and good news for fans of a livable climate (and soccer):

The Bad News

Yes, more gas guzzled in the short run.

It now costs less to drive your carbon-spewing car, so people are driving their cars more. Of the $13 million Americans saved on gas in November and December, nearly $5 million was spent on simply buying more gas, according to a report from retail consulting firm Customer Growth Partners. And it’s cheaper for companies to ship products long distances. Food grown far away with diesel-burning machines and petroleum-based fertilizers gets less expensive to produce relative to locally grown and distributed organic food. As a result, oil-soaked goods and services get cheaper and cost-conscious consumers buy more of them.

More oil burned over the long haul, too.

Companies chiefly concerned with the next two quarters’ profits are investing in petroleum-powered vehicles and machinery that will last decades. Meanwhile, according to David Hughes, fossil fuel fellow at the Post Carbon Institute, politicians uninterested in futures beyond the next election could push through infrastructure projects — new roads, pipelines, and unbelievable transportation megaproject fusterclucks — that keep the oil economy humming for years to come. “For these long-term issues, we need some long-term planning,” says Hughes.

Clean energy could struggle to compete for investment.

Energy and transportation wonk Roland Hwang, of the Natural Resources Defense Council, says that inexpensive oil “creates challenges in the marketplace for clean energy.” In other words, all those investments in oil-burning stuff (see above) might crowd out smarter technologies. Hwang says it’s “all the more important we have clean energy standards in place,” such as regulations for low-carbon fuels and the proportion of utilities’ electricity supply that must come from renewable sources, policies that keep us on the right track even as the volatile world oil market plays seesaw with prices. Thankfully, clean energy did have a monster year in 2014, as total investment grew 16 percent. But more billions toward clean energy doesn’t mean fewer gigatons of carbon emissions. Thanks, growth.

More deadly car accidents.

The Federal Highway Administration confirms that people drive more when gas is cheaper. What’s worse: an increase in cars on the roads also means more accidents. Guangqing Chi, a sociologist at South Dakota State University, told NPR that “a $2 drop in gasoline price can translate to about 9,000 road fatalities per year in the U.S.” Yikes.

The next two World Cups could be in financial trouble.

Oh no! Russia, slated to host the global soccerfest in 2018, loses about $2 billion in revenue for every dollar drop in the per-barrel price of oil. It cost Brazil over $11 billion to host the World Cup last year, and Russia will likely need to spend far more, since a big chunk of the country’s expenditures will inevitably be lost to corruption (if the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi were any indication). And Qatar, which will host the 2022 tournament, is even more oil-dependent than Russia. It expects to spend more than $200 billion on the World Cup, and it claims the plummeting price of oil will not alter its grand plans, even though the nation’s finances come mostly from selling crude on the global market. We shall see.

The Good News

Oil booms could go bust.

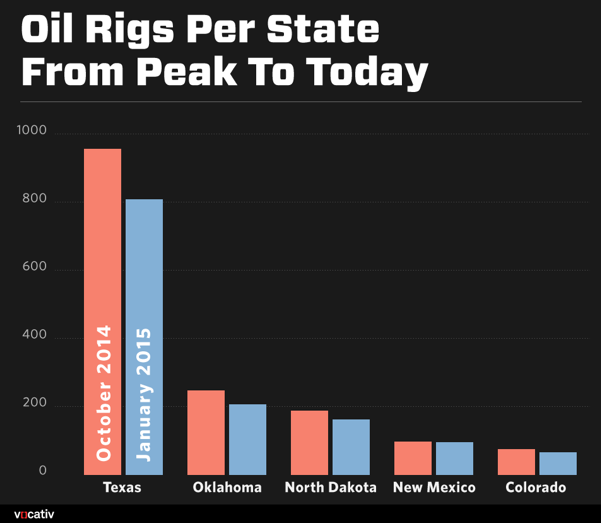

Times are getting tough for the companies digging up expensive, unconventional crude in the Alberta tar sands and the fracked shale formations of the U.S. Last week I wrote about how the U.S. Energy Information Administration does not expect petroleum production to slow at all in North Dakota, despite the precipitous price fall. Turns out, those numbers might have been some optimistic fudging — something Hughes has seen from the U.S. government time and again. If you look at the database the EIA normally uses, says Hughes, “drilling permits dropped 50 percent year-over-year from October 2013 to 2014, [which] should equal a slowdown in drilling.” Production from shale-oil wells declines fast: Output drops 70 percent in just the first year of pumping. So the industry needs to drill thousands of new holes in the ground each year just to keep a steady stream of oil flowing, which means a slump in new activity could limit oil output pretty quickly. Even Fortune says the shale oil revolution is “in danger.” The chart below, from Vocativ, shows drilling rig decline over the past three months, evidence that the recent U.S. oil spurt has been only a fairy tale.

Data: Baker Hughes. Chart: Vocativ

Other sectors of the fossil fuel industry are getting squeezed, too.

Vox and others are questioning whether Keystone XL even makes financial sense at today’s low oil prices. And the natural gas industry could be threatened, too, since gas from oil wells makes up one-fifth of total U.S. production. In fact, North American energy companies have slowed down new pipeline construction so much in response to the oil price plunge that U.S. Steel, the country’s second-biggest producer of the material, is idling two big pipe-manufacturing plants. Layoffs are bad for those whose livelihoods rely on the fossil-industrial complex — oil giant Halliburton just announced some job cuts as well — but these shocks underscore the silliness of tying people’s well-being to turbulent global commodity markets, and the need to create new local economies in places where fossil fuels have long been the only business in town.

Bring on the carbon tax!

When the public catches wind of any sort of proposed energy tax, the first question is, “What’s going to happen to gas prices?” When gas prices are already low, the answer is not so alarming. Charging producers $25 per ton of CO2 would raise the price of a gallon of gasoline about $0.25, which might not elicit loud complaints while prices at the pump are more than a dollar cheaper than just a year ago. As painful as it is to praise very serious economist Larry Summers, the U.S. Treasury secretary under Clinton, we endorse his call to “Let this be the year when we put a proper price on carbon.” Let’s hope it will help ignite a very serious debate about the “true” social cost of carbon (as if some correct price could be calculated objectively) and who should get the revenue from such a policy (us, please). Even Senate Republicans like Bob Corker are advocating a gas tax hike, though their motives have more to do with resuscitating the dwindling Highway Trust Fund than moving toward a low-carbon future.

More cash in people’s pockets.

Cheap oil means wealth is redistributed from oil producers to consumers, which is progressive! As one Bloomberg View columnist puts it: “Because energy spending constitutes a bigger part of the budget for lower-income families, lower oil prices help counter some forces that have worsened the inequality of income, wealth and opportunities.” While families might spend some of that extra cash on oily things (see cons above), we won’t ultimately fix the climate crisis unless we tackle economic inequality. In fact, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass) says climate change and inequality are really just one issue: “a rigged system, where a handful of people are able to reap benefits at the cost of everyone else.” Right on.

Cheap oil buys time for the climate movement.

Climate activists are pushing hard to make sure that infrastructure isn’t built to exploit dirty energy sources that shouldn’t be extracted at all. If drilling for cheap crude slows down now, there’s more time to enact policies that permanently lock up oil in the soil (and tar sands). People worried about peak oil chaos would be pleased to see drilling deceleration, too: “Putting the brakes on now, maintaining a plateau, and ramping down at a slower rate is preferable to dealing with the steep decline later,” says Hughes. And that decline will come even quicker if we’re going to leave some oil underground to, you know, save the climate. “The bottom line is it is a bubble, if you look out a decade or so,” Hughes says about the oil boom from shale. “It is a short-term bonanza.”

—

Your head spinning yet? Ours too. The truth is we don’t quite know yet how cheap oil today will affect the climate tomorrow. But ultimately, for the planet’s sake, we need to find something other than oil to fill our economy’s tank. Here’s hoping Congress can increase the gas tax (nobody’s holding their breath for national carbon pricing, but one recent bill proposes taxing gasoline based on emissions) and activists successfully block Keystone XL and some oil-by-rail projects.

Now that would be some good news.