It turns out even a global pandemic can’t keep humans from spewing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. The COVID-19 outbreak is far from over, but countries around the world are reopening anyway — and triggering a global surge in carbon emissions. The main reason? People are taking refuge from the coronavirus in their cars.

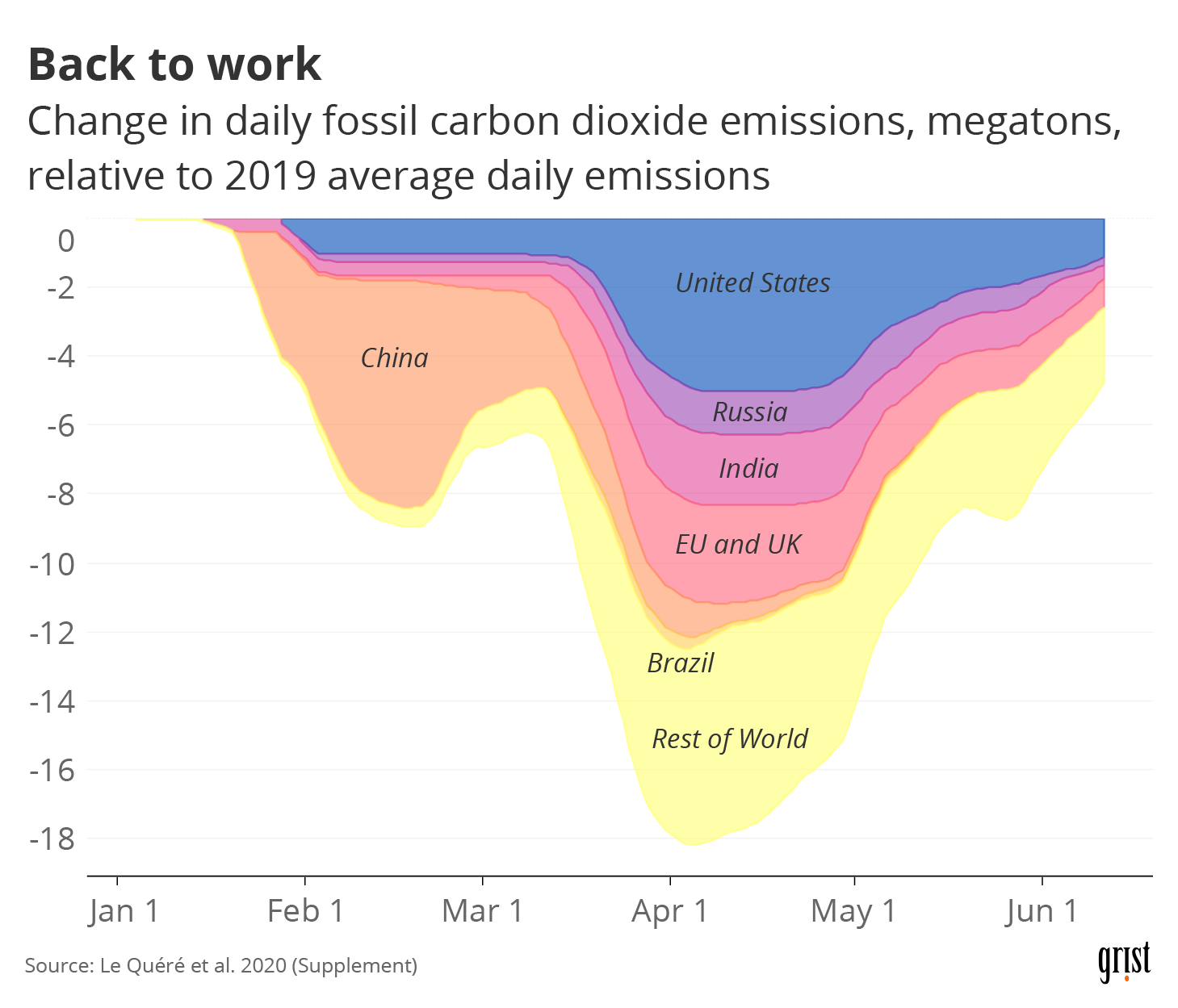

According to a recent update of a study originally published in Nature Climate Change, fossil fuel pollution has bounced back rapidly as lockdowns have started to lift around the world. In early April, when billions of people were sheltering in place, global daily carbon dioxide emissions were 17 percent lower than they were in 2019; now, it’s almost as if the lockdowns never happened.

Clayton Aldern / Grist

“We’ve already come pretty close to where we would have been last year,” said Rob Jackson, chair of the Global Carbon Project and one of the co-authors of the study. He said daily global emissions are now just 5 percent less than the daily average in 2019 — and will likely continue to climb.

It’s all because of traffic, Jackson said. The dip in emissions during the lockdowns mostly came from transportation, as people stopped driving to work and taking flights. (Other emissions, like those from electricity, heat, and industry, continued apace.)

But as the world slowly returns to something resembling “normal,” traffic is on the rise. In the U.S., passenger vehicle travel dropped by almost 50 percent in early April; now it’s back to 90 percent of February levels.

Fear of the coronavirus is also pushing people to get in their cars, instead of taking public transit. Last month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released guidelines encouraging people to drive to work solo, instead of taking the bus or the subway. (They quietly revised those guidelines two weeks later to also encourage biking or walking.) Last Monday, 800,000 people rode the New York City subway, the highest number since March — but that’s still only 15 percent of normal.

The researchers still expect emissions for the whole of 2020 to be down 4 to 7 percent compared with last year, depending on the pace of reopening. But that’s not even close to enough to slow down climate change. Keeping global warming below dangerous levels would require a 7.5 percent drop in emissions every year.

Jackson said he hopes that there will be some lingering positive effects from the shutdown, like cities making streets more pedestrian-friendly or workplaces incorporating more telecommuting. But, he said, scientists always knew the drop in emissions wouldn’t last.

“People want to move on with their lives,” Jackson said. “We can’t reduce emissions just by locking people at home.”