Environmental justice featured more prominently in the 2020 election than it did in any other presidential election in U.S. history. Now that Democratic nominee Joe Biden — who schooled his opponent on the subject during the final presidential debate — has secured the electoral votes to become the next commander-in-chief, environmental justice advocates across the country are expressing excitement about the steps the new administration is likely to take to protect vulnerable communities from the effects of pollution and climate change. This optimism is guarded, however, given the immense challenge of reversing the environmental damage abetted by the administration of President Donald Trump.

“The presidential election results are a critical victory for the climate movement,” Arielle Swernoff, lead communications strategist at the environmental justice coalition New York Renews, told Grist. “We now have a president we can effectively organize to act swiftly and justly on climate, and to take much-needed federal action to build a just, green recovery to our current interlocking COVID-19 and climate crises.”

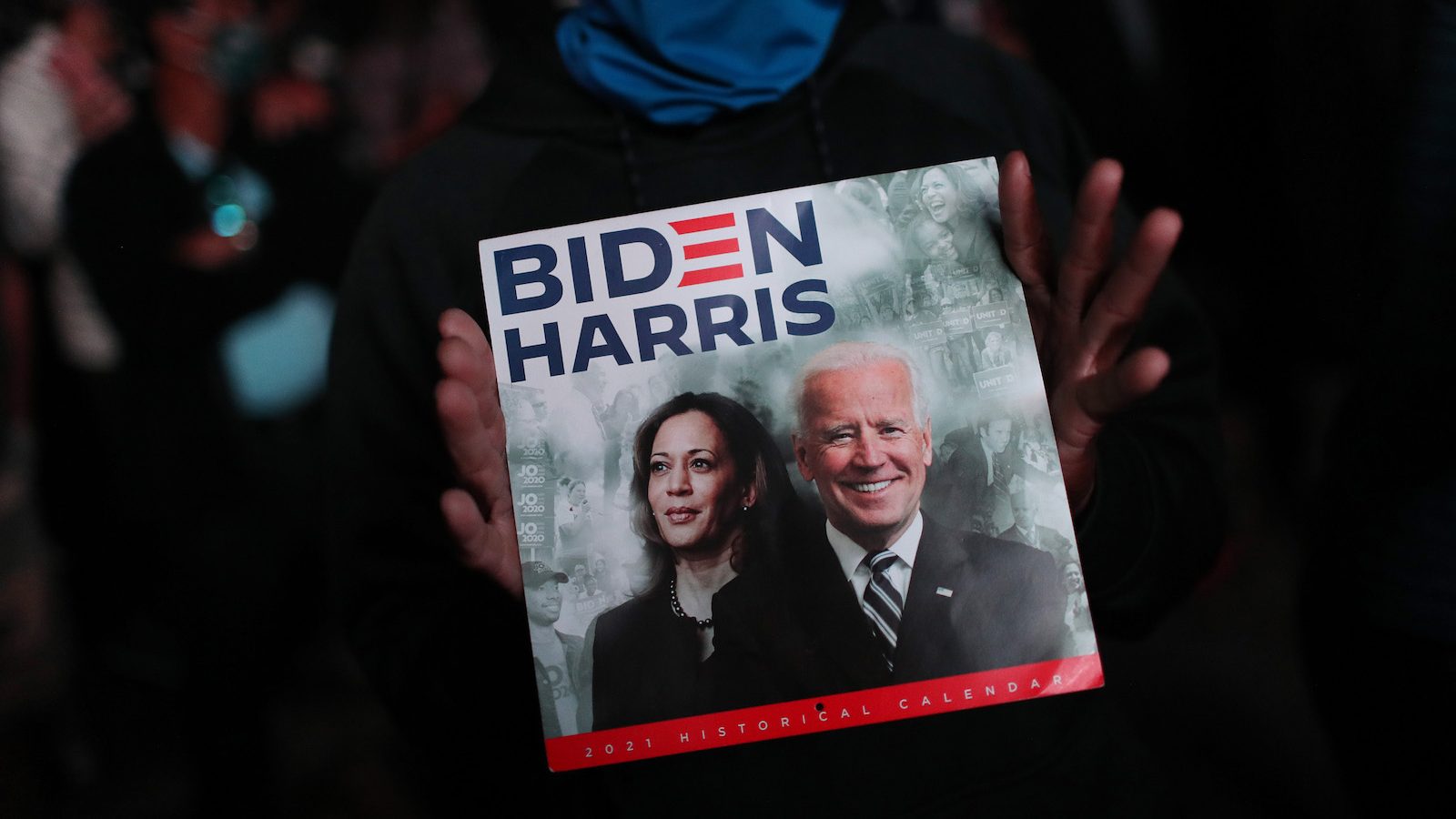

It’s no surprise that advocates are glad that Biden emerged victorious: His campaign released a detailed environmental justice plan acknowledging that low-income communities and communities of color have endured disproportionate harm from climate change and environmental contaminants for decades. (The plan prioritizes objectives outlined in the environmental justice legislation introduced this summer by then-Senator Kamala Harris, who is now the incoming vice president.) Both his $2 trillion dollar clean energy plan and his plan for tribal nations also prioritize environmental and climate justice. The new administration has indicated that it plans to hold polluters responsible for their contributions to the underlying health conditions that have put Blacks, Latinos, and Indigenous groups across the country at greater risk of dying from COVID-19.

North Carolina environmental justice advocate Omega Wilson told Grist he was thrilled that Biden and Harris won the election — but it’s a victory tempered by the sobering reality of the work that is still ahead. At age 70, Wilson has lived long enough to witness the election of multiple presidents who sought to advance racial equity, from John F. Kennedy to Barack Obama. These presidents were swept into office with the support of some of the poorest and most disadvantaged communities, he said, yet very few of the promises made on the campaign trail translated into healthier and more prosperous lives at the local level.

“People are voting hoping that things are going to change where they live, where they walk, where they work,” said Wilson, who co-founded the West End Revitalization Association, a community development corporation in Mebane, North Carolina, that has worked since 1994 to convince local municipalities to deliver basic public services such as sewer lines, city water lines, and paved streets to neglected, historically African American communities.

The question, said Wilson, is whether the Biden-Harris administration can take corrective action at the ground-level to provide safe environments and clean water to all Americans, and to reduce exposure to hazardous waste, pollution, and landfills in communities of color. It’s a point Wilson said he’s emphasized for almost three decades working on environmental justice issues at the local, state, and federal levels.

After the election of President Barack Obama, Wilson was selected to participate in a private forum of environmental justice experts gathered to advise the incoming president on how to address environmental justice and racial disparities across the country. After President Trump took office, Wilson watched with dismay as Trump dismantled or rolled back safeguards put in place under Obama to protect waterways, reduce emissions, and provide oversight of polluting industries. Twelve years after that forum, he understands how much work it will take — not just to reestablish the standards set under the Obama administration, but to set new priorities as well.

So after the major news outlets announced on Saturday that Biden had won enough electoral college votes to assume the presidency, Wilson got right to work sending emails, setting up phone calls, and discussing how to help the new administration tackle its priorities, such as passing environmental justice legislation in Congress. It’s meant late nights and early morning hours fueled by a lot of coffee and plagued by furrowed brows and headaches, he noted wryly.

“My excitement and my wife’s excitement and some of my friends’ excitement is not so much jubilation like we see on television,” said Wilson. “My mind goes directly back to the work we have to do to create a measurable outcome at the ground level.”

Trucks drive through the Ironbound district in Newark, NJ. Yana Paskova / The Washington Post / Getty Images

In states like New Jersey, where environmental justice advocates have successfully pushed for the passage of more stringent environmental laws to protect public health and communities of color burdened by decades of pollution, activists hope that a Biden-Harris administration will be more aligned with those communities that are already taking action to hold polluters accountable.

Earlier this year, New Jersey state legislators passed a landmark law that requires the state’s Department of Environmental Protection to consider the cumulative effects of pollution on overburdened communities when considering granting permits to industrial facilities such as power plants and incinerators. However, even when activists make progress at the municipal and state level, their efforts can be stymied in cases where the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has the final say, such as in the oversight of contaminated Superfund sites.

“If we have a federal government that’s also doing what we’re doing locally and statewide, it sends a clear message [to polluters] that you’re not going to be allowed to come in and do business as you always have done in the past,” said Kim Thompson-Gaddy, an environmental justice organizer for Clean Water Action of New Jersey, a grassroots organizing group.

Thompson-Gaddy, who also serves as vice chair of the state Department of Environmental Protection’s Environmental Justice Advisory Council, said that she’s elated to have a president-elect who has prioritized restoring critical environmental and public health protections, citing Biden’s plans to address water pollution and rejoin the 2016 Paris Climate Agreement. “Just to start there is a breath of fresh air,” said Thompson-Gaddy. But she’s especially heartened that Biden says he wants to hold polluters accountable by enforcing existing environmental laws, because that enforcement will complement the work activists are doing in their communities to reduce emissions and address contamination.

In Newark, home to the country’s third largest port, frontline communities experience both the benefits and the downsides of a port that’s both the economic engine for the state, but also what Thompson-Gaddy calls a “death zone” for people who live in nearby neighborhoods such as South Ward. Community organizers have worked to mobilize and inform residents on the importance of removing lead from water pipes that provide drinking water, as well as the need to establish zero-emission zones and convert the pollution-heavy diesel trucks that frequent the port to an all-electric fleet.

An aerial view of the Port of Newark, New Jersey. Smith Collection / Getty Images

“When we begin to have honest conversations about cumulative impacts and making sure the polluters are going to be held accountable, that’s the change that we need to see. That could be transformative in our neighborhoods and in our cities,” said Gaddy, who is also coordinator of the South Ward Environmental Alliance in Newark.

Judith Enck, a former EPA regional administrator, is also cautiously optimistic for the incoming Biden-Harris administration. She believes that achieving environmental justice in the U.S. is possible, but she wants to see special efforts put towards protecting frontline communities of color from the climate crisis.

“Every single thing that the EPA and other federal agencies do, must be viewed through the lense of environmental justice and children’s health,” Enck wrote in an email to Grist. She emphasized that the shift toward environmental justice needs to happen in other government agencies besides the EPA, such as the Department of Justice, the Treasury Department, and any other agency that funds future economic development projects.

“Every environmental enforcement case that is filed needs to be decided in a way that answers the fundamental question: What will this decision mean for the health and safety of people living in low-income communities and communities of color?” wrote Enck, who is now a visiting professor at Bennington College in Vermont.