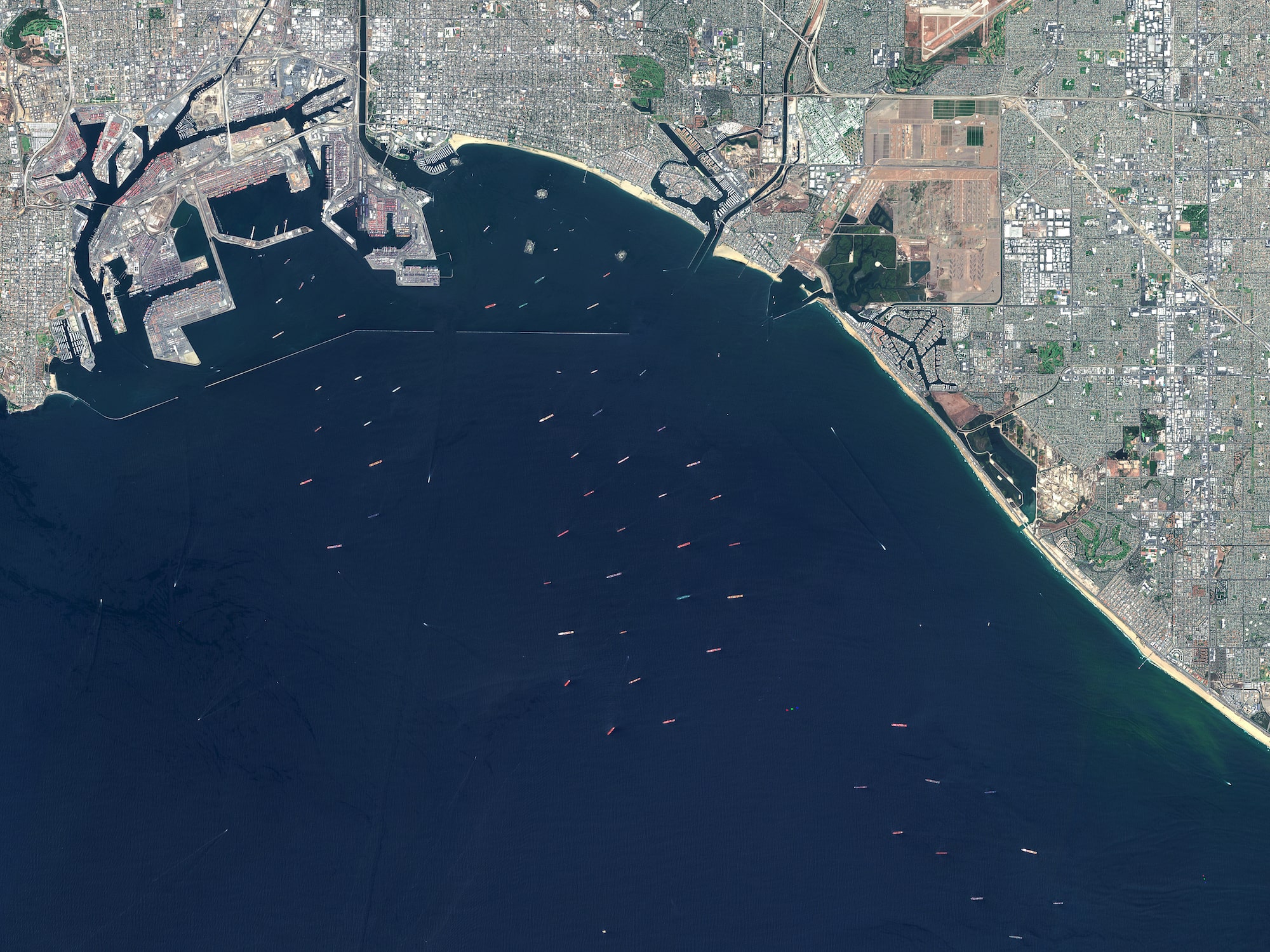

The record crowd of cargo ships off the coast of Southern California isn’t just making it harder to find furniture, children’s toys, or pet food in stores across the country. It’s also driving a spike in dirty exhaust that threatens the health of vulnerable communities nearby, according to California regulators.

Dozens of vessels are running their secondary diesel engines as they anchor or drift near the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, the ninth-busiest shipping complex in the world. The logjam first emerged last fall as a result of Covid-related supply chain disruptions and, now with the holiday shopping season approaching, is only getting worse.

“If you go down to the harbor, you can see the ships going out for several miles, and you can see the emissions coming out of their smokestacks,” said Taylor Thomas, co-executive director of East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice. The organization works in East Los Angeles, Southeast Los Angeles, and greater Long Beach — areas where many Black and Hispanic people are exposed to industrial pollution and suffer higher rates of asthma. Thomas herself grew up in West Long Beach, about a mile and a half from the port.

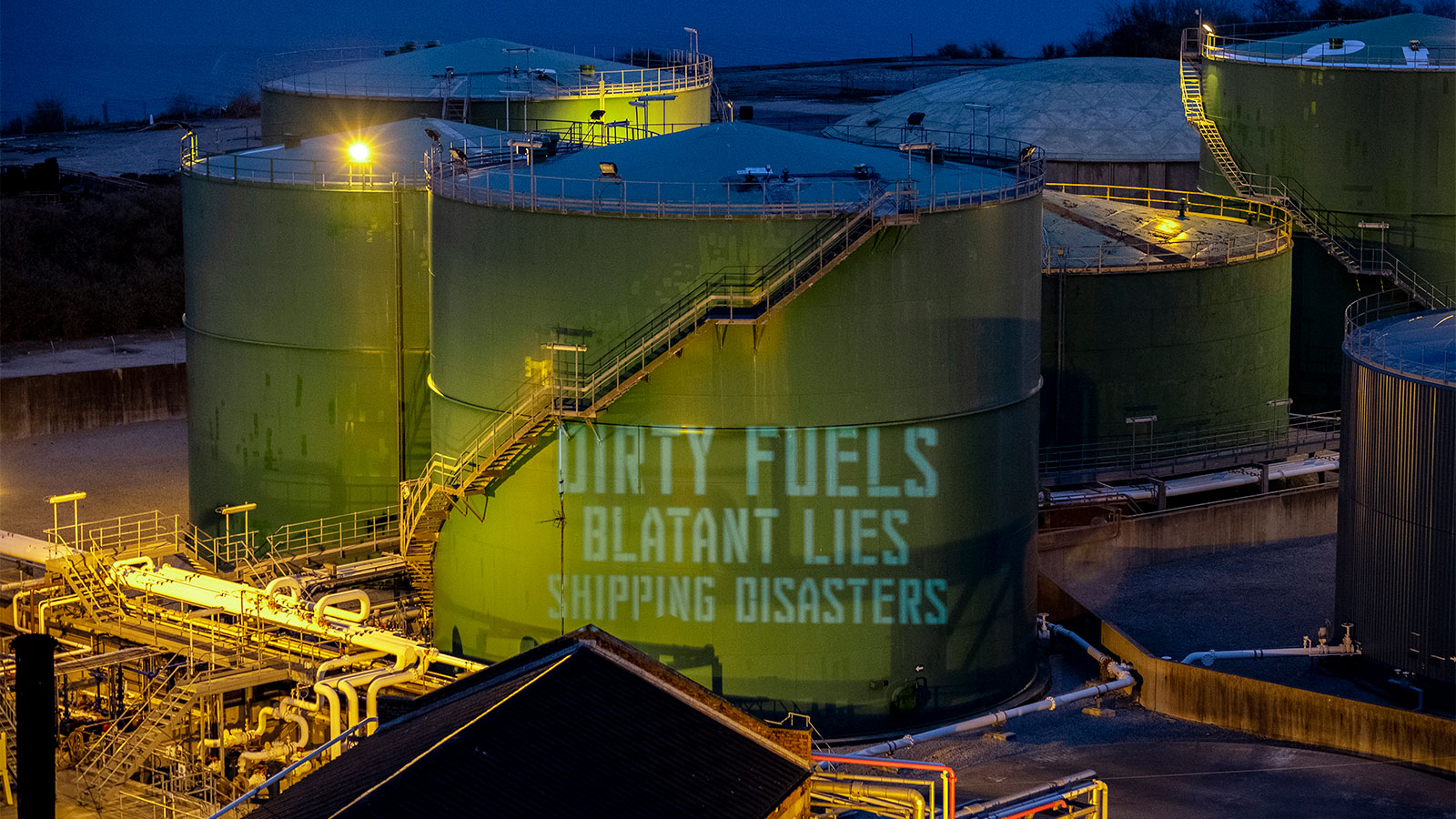

Cargo ship congestion might also be to blame for another environmental hazard: the massive oil spill just down the coast in Orange County. Officials say they are investigating whether a ship’s anchor struck a crude oil pipeline late last week, resulting in a 126,000-gallon leak that’s smothering beaches and wildlife.

Experts say the traffic jam along the Southern California coast and at other major ports around the country may be more than a pandemic-era blip. U.S. retail imports and e-commerce sales are expected to soar in coming years, and emissions from vessels, heavy-duty trucks, trains, and port equipment are expected to climb in tandem, so long as all those engines continue burning fossil fuels.

“This should not necessarily be considered as a temporary issue” but rather a long-term challenge, said Sam Pournazeri, who heads the mobile source analysis branch at the California Air Resources Board, or CARB, in Sacramento. “We really need to think about cleaning up the ports and going to zero-emissions across the freight sector, wherever feasible, to avoid these kinds of air quality issues.”

On Wednesday, 62 container ships were anchored a few miles off the coast of Los Angeles and Long Beach, up from a pre-Covid average of roughly a single ship, said Captain Kit Louttit, who monitors port traffic for the Marine Exchange of Southern California. In mid-September, as many as 73 container vessels were waiting to pull into port. Ships stuck in limbo run their smaller auxiliary engines to keep the lights on, power communications equipment, and cool down refrigerated shipping containers. The vessels burn low-sulfur diesel fuel, which is cleaner than the “heavy fuel oil” ships use out at sea but nonetheless contributes to air pollution.

From October 2020 to March 2021, when supply chain bottlenecks caused the first major backup, container vessels near Los Angeles and Long Beach caused a sharp increase in emissions of cancer-causing particulate matter and smog-forming nitrogen oxides, which can damage people’s lungs and trigger asthma symptoms, according to the state resources board. On land, emissions from heavy-duty trucks and locomotives also rose significantly over the same stretch as the ports handled more than 50 percent more cargo than they did in 2019, before the pandemic hit.

The agency hasn’t tallied emissions from port congestion in recent months. But, given that twice as many container ships are idling today than at the highest point in the spring, overall pollution has likely doubled as well, Pournazeri said. And the bottleneck isn’t expected to clear anytime soon. Port executives in California said supply chain snafus, worker shortages, and little space in warehouses could ensnarl container shipping through next summer.

Rising pollution from the area’s ports will make it harder for Southern California to comply with federal clean air rules, including a 2023 deadline to cut smog-forming emissions, according to CARB. It will also ensure that people living in neighborhoods near the ports face continued exposure to harmful contaminants. In the communities where the East Yard group organizes, residents already experience higher incidences of heart and lung diseases, cancer, reproductive health issues, and skin conditions as a result of smog and ozone from highways and ports, Thomas said

Without recent efforts by regulators, pollution from ongoing congestion would likely be even worse, said Bonnie Soriano, CARB’s branch chief for freight activity. State and federal agencies, as well as port operators, have been working to curb pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from cargo shipping. California requires ocean-going vessels to switch to low-sulfur fuel within about 28 miles of the coastline. And container, cruise, and other types of vessels must cut their auxiliary engines and plug into shoreside electricity supplies — or use emission control technologies — once they’ve docked.

Starting next year, the agency will begin evaluating how to reduce emissions from anchored vessels. That might involve deploying barges mounted with fuel cells, which idling ships could plug into, or using systems that capture and clean ship exhaust out in the bay.

Still, getting ocean-going cargo ships to ditch fossil fuels entirely requires a global effort, since vessels operate in many different countries.

A container ship piled high with T-shirts, electronics, or appliances needs to be able to use the same fuel when it departs from, say, Taiwan as when it arrives in California, Singapore, and the Netherlands. The International Maritime Organization, the United Nations agency which regulates the global fleet, has adopted policies to curb carbon dioxide emissions and reduce fuel consumption from ocean-crossing vessels. But massive investments are needed to develop not only new types of ship technologies but also to build the infrastructure to produce and distribute alternative fuels, Soriano said.

With that in mind, Ocean Conservancy recently outlined a plan for creating a zero-emission shipping lane between five major ports on North America’s West Coast, including Los Angeles and Long Beach. Each location could harness renewable energy resources to produce hydrogen, a carbon-free fuel that can directly power certain ships and port equipment, or be used to create other fuels like green ammonia and methanol. The idea is to create a regional market that can serve as a model worldwide.

“There’s an opportunity to influence and drive decarbonization in other zones just through the example that [the U.S. and Canada] will be setting,” said Victor Martinez of Ricardo Energy & Environment, a consulting firm that produced the Ocean Conservancy report.

Other environmental groups are working to clean up shipping by pressuring the biggest users of oil-guzzling freighters: major retailers like Amazon, Walmart, and IKEA. A recent report commissioned by Pacific Environment and Stand.earth found that importing some 3.8 million shipping containers’ worth of cargo on oil-guzzling freighters generated as much carbon dioxide emissions as three coal-fired power plants. The groups are urging retail giants to commit to using zero-emission ships within the decade.

Thomas said that building renewable energy projects and alternative fuel infrastructure for cargo ships could bring more jobs to the East Yard communities, which have higher rates of unemployment. “There are ways for us to create a new world that relies on jobs and industries that don’t produce harm,” she said.