On a Saturday in early October 2011, Mike Smith was fishing on a pond on his property northwest of Dallas when he noticed a strange odor that smelled like diesel. Texas was in the middle of a prolonged drought, and the odor was emanating from a dried-out section of the pond. When Smith dug into the spot, a yellowish liquid gurgled up. Assuming that the liquid was likely a petroleum product, Smith contacted Burlington Resources Oil and Gas, which operated wells on his property, to report what appeared to be a leak. Burlington referred the matter to Targa Resources, a pipeline company that operated the lines transporting oil and gas from Burlington’s wells.

Despite being required to report the contamination under local environmental rules, neither Burlington nor Targa notified the Texas Railroad Commission, the agency responsible for oil and gas oversight in the state. They also did not conduct technical assessments to determine the extent of contamination or its cause. Instead, after Smith filed a complaint to the Commission, both companies proceeded to deny responsibility for cleanup. The dispute dragged on for the next seven years. After agency staff determined that Targa’s pipelines were the likely cause of contamination, Targa cleaned up the surrounding soil. In 2019, the commissioners denied Smith’s request for additional testing and monitoring and released the two companies of their responsibilities for cleanup without issuing any fines.

It might have been just another example of a painfully slow regulatory agency — were it not for the commissioners’ financial interests in the companies under investigation. Two of the three commissioners that signed off on the cleanup held stock in ConocoPhillips, Burlington’s parent company, while the case was being heard. In 2019, commissioners Wayne Christian and Christi Craddick sold up to 99 ConocoPhillips shares, according to personal financial disclosures. Craddick also reported holding shares in Targa Resources worth up to $4,042 at the end of 2019. From 2015 to 2021, the two commissioners collected a grand total of $31,000 in campaign contributions from ConocoPhillips and Targa’s political action committees and executives employed by the companies.

Regulators who hold a financial stake in a company while simultaneously making official decisions that might affect its bottom line are involved in a clear conflict of interest. Such conflicts are not uncommon at the Texas Railroad Commission, or RRC, which happens to be one of the most powerful agencies charged with environmental protection in the country’s oilfields. According to new and forthcoming reports by the government accountability nonprofit Texans for Public Justice and Commission Shift, another Texas-based nonprofit that monitors the Railroad Commission, all three current commissioners are subject to conflicts of interest.

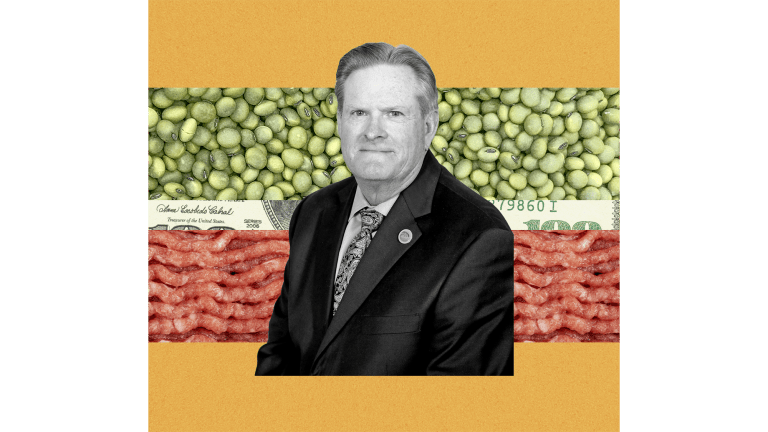

To start with, more than two-thirds of their approximately $10 million in campaign contributions since 2015 have come from the oil and gas industry. Last year, commissioners Craddick and Christian held stock worth hundreds of thousands of dollars in dozens of oil and gas companies, including Shell, Diamondback Energy, Kinder Morgan, and ConocoPhillips. Commissioner Jim Wright, who joined the commission in 2020, has had financial stakes in more than 18 oilfield wastewater disposal companies. Wastewater from oil and gas operations is regulated by the RRC, and operators that Wright’s companies conduct business with have had cases considered by the agency.

“We need the commissioners to be making decisions that are best for the people of Texas and not always defaulting to what financial interests want from them,” said Virginia Palacios, Commission Shift’s executive director and a co-author of the report.

The RRC is responsible for regulating the oil and gas industry in the nation’s largest oil-producing state. It is headed by three commissioners who are voted into office for six-year terms in statewide elections. With regulatory authority to cap production in oil fields, require environmental safeguards and cleanup, and levy millions of dollars in fines against wayward actors, the agency wields enormous power over the industry.

That power, however, is seldom used. In 2011, after a brutal winter storm led to blackouts in the state, federal regulators recommended weatherizing pipelines and fossil fuel infrastructure to prevent another similar disaster. But the RRC didn’t heed those warnings, and Texas was once again plunged into darkness earlier this year when Winter Storm Uri made landfall. More recently, it has permitted operators to burn off more than a million cubic feet of natural gas every day, a practice that releases billions of pounds of climate-warming pollutants.

As a result, the agency is described by watchdog groups and advocates as “captive” to industry interests, rarely penalizing polluters or setting strict pollution limits that protect the health and safety of Texans.

That perception is underscored by the fact that commissioners are allowed to accept unlimited campaign contributions from the very industry they oversee year-round, in contrast to oil and gas regulators in nearby states. For instance, members of the Oklahoma Corporation Commission are required to divest of any oil and gas interests before serving on the agency, and campaign contributions are capped at $5,000. No such requirements exist for the RRC commissioners.

Personal financial disclosures that commissioners are required to file lack specificity about the volume of holdings and nature of income, and the current upper limit for disclosure of a given interest is “$44,630 or more,” which obscures the extent of commissioners’ financial ties to any given entity. The agency’s recusal policies require commissioners to abstain from decisions in which they have “a personal or private interest,” but what constitutes such an interest isn’t clearly spelled out. Texas rules reference the state constitution, but the constitution provides no additional guidance. Commissioners also decide whether or not to recuse themselves when a conflict of interest exists. If they fail to do so, the attorney general can step in to enforce the policy, but Texas’ current attorney general is himself mired in ethics scandals.

Despite their many financial relationships with oil and gas companies, the commissioners have only recused themselves on five occasions out of hundreds during the past six years, according to Palacios. In 2016 and 2017, Commissioner Craddick recused herself in two cases that did not involve companies that she had a financial interest in. In the 2016 case, she did not provide an explanation for her recusal, and in 2017 she recused herself from voting on whether to involve the state attorney general in the dismissal of the agency’s executive director (a dismissal that another commissioner accused her of orchestrating).

“It’s strange, because they don’t seem to be interpreting these rules when it comes to their own financial interests,” said Palacios.

In a statement to Grist, Commissioner Christian said his “entire investment portfolio consists of mutual funds and other similar accounts controlled without my input by a third-party manager,” and that his personal financial statements are “a snapshot in time and could be different on any given day.” He accused Commission Shift of being a “biased anti-oil and gas special interest group.” Commissioner Wright said that he bases his decisions on what is best for Texans.

“Upholding the public’s trust, not to mention my own personal integrity, is important to me, and I am committed to following all rules and regulations set forth under state law and administered by the Texas Ethics Commission,” he said. Commissioner Craddick’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Ultimately, ethics rules matter because they improve public trust in the agency, according to Palacios. While there are no documented instances of a quid pro quo, Commission Shift’s reports document several instances in which the public may question the impartiality of the commissioners, given they stand to benefit financially from their decisions.

A Corpus Christi-based waste disposal company illustrates one such instance. Blackhorn Environmental Services handles non-toxic oil and gas waste and had a permit up for renewal earlier this year. In the lead-up to the commission’s vote on whether or not to renew the permit, local residents who live near the Blackhorn site and had been experiencing adverse health effects protested against the facility. They suspected that fumes from the facility and heavy trucks transporting waste to and from the site were responsible for the runny eyes, burning throats, and other health issues they were facing. Commissioner Wright, who owns two companies that used the Blackhorn site to dispose of oil and gas waste, voted in favor of renewing the facility’s permit.

“It just creates a perception of conflict, and it’s really frustrating for people who are facing pollution impacts,” said Palacios. “They’re raising their kids out there. If they file a lawsuit, how long is that lawsuit going to take? And what is it going to take for the Railroad Commission to create the conditions where people can be healthy and live their lives?”