The Getty Center in Los Angeles is a white-walled fortress. The charred trees and ash-gray soil surrounding the museum complex, detritus from the Getty Fire, make clear what threat it’s built to protect itself against.

In late October, a strong wind gust broke off a branch of a eucalyptus tree and threw it into a power line, sparking the Getty Fire — or so the theory goes. Helicopters swooped in to douse the flames, and firefighters set up a staging area at the Getty. The blaze ripped through nearby neighborhoods, forcing thousands of people to evacuate and destroying a dozen homes. But the fire barely touched the museum.

The Getty’s collection of ancient Greek sculptures, thousand-year-old manuscripts, and irises painted by Vincent van Gogh might be one of the best protected in the world. In the case of a wildfire, a tank filled with more than 1 million gallons of water can soak the perimeter, creating a modern-day moat. (Before the Getty Fire, it snuffed out the Skirball Fire in 2017.) The museum has thick walls made of travertine, a flame-resistant material used for fire pits. And if smoke manages to creep into the museum, a special air-pressure system can push it out.

The Getty can afford these protections because it’s one of the richest museums in the world — and that’s all thanks to oil money. The museum owes its existence to J. Paul Getty, the famous oil tycoon and self-described art-collecting “addict.” The Getty Trust, which he founded in 1953, is worth more than $10 billion.

The Getty Center stands behind a burnt hillside in late October. FREDERIC J. BROWN / AFP via Getty Images

Across the country, museums are working to protect their irreplaceable collections from the ravages of climate change: rising seas, more frequent flooding, and worsening wildfires. In an ironic twist, many of these institutions, through their boards, funding sources, and fortunes amassed by their founders, are closely tied to the fossil fuel companies that have contributed the most to the problem.

ExxonMobil, for instance, is one of the most charitable corporate donors on the planet, as well as the fourth-biggest polluter. The company has contributed more than 3 percent of total global carbon dioxide emissions since 1965. Last year, it gave $2 million to arts and culture organizations in the United States. Most of the recipients are in its home state of Texas — like the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas or the Austin Symphony Orchestra Society — but Exxon spreads its largesse around, supporting the Anchorage Museum in Alaska and recently giving $850,000 to the Smithsonian Institution for a traveling exhibit about African-American motorists in the mid-20th century.

Though sources for this story didn’t know of any database of corporate donations, the sponsorship pages of the country’s prominent art museums reveal a lineup of the world’s oil giants. Shell has sponsored exhibits at The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., one of the country’s biggest art museums. (Exxon has, too.) It also sponsors the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. The Denver Art Museum counts Duncan Oil among its partners. ConocoPhillips donated $1.9 million to art programs last year.

These donations are coming under increased scrutiny, as more artists and activists say that it’s time for cultural institutions to ditch “dirty money.” The demands have grown out of the broader divestment movement, which uses social pressure to prod universities, banks, and local governments to cut their ties to fossil-fuel companies. Activists want museums to look beyond their own walls and use their resources to educate the public about the climate crisis. The thinking is that museums could play a more meaningful role in imagining a future free from fossil fuels … if they weren’t dependent on money made from the exploration, refining, and distribution of them.

Plastering an oil company’s logo on the wall of an art museum might not seem like a big deal at first glance, but that sort of branding is critical for getting popular support. “That logo, that name, is part of fossil fuel infrastructure,” said Imani Jacqueline Brown, an artist in New Orleans (and member of the Grist 50 class of 2018). “It is as essential as the wellhole, as the pipeline, as the transportation barge, as the refinery.”

The Jazz & Heritage Festival is an annual tradition that draws hundreds of thousands of visitors to New Orleans, along with famous musicians like Katy Perry and Carlos Santana. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Shell stepped in to be the festival’s lead sponsor. This year, its logo was plastered on performance tents, entryways, and the wallpaper behind the press conference podium. “Shell continues to invest billions of dollars into safely running and growing our operations [in New Orleans],” says the company’s page touting its sponsorship. “We can do this because people know us and trust us — Jazz Fest is a big part of how we earn that trust.”

Katy Perry performs during the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival 2019. Jeff Kravitz / FilmMagic / Getty Images

It’s a story as old as the arts. The rich and powerful have long used their means to support artists and shape the works that they produced. The Medici family’s banking empire helped spur on the Renaissance in 15th century Italy. They were patrons of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, who painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and created the 17-foot sculpture of David. These works bolstered the Medicis’ reputation, showing off the family’s refinement and commitment to the cultural legacy of Florence.

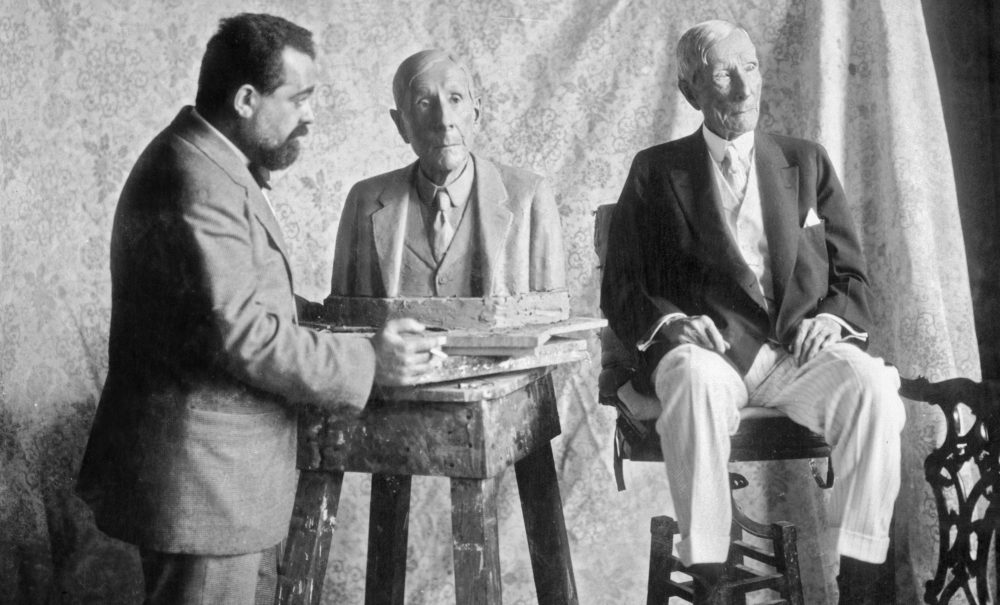

The same spirit drove the Rockefellers. John D. Rockefeller built Standard Oil in the late 1800s, leaving a fortune that has helped launch art museums in the United States. The Museum of Modern Art in New York City was cofounded by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, who married John’s son, just days after the crash that started the Great Depression. In the same era, The National Gallery of Art was founded by Andrew W. Mellon, a Pittsburgh banker who made some of his riches in oil and coal. Fossil fuels have made a bunch of Medicis.

Philanthropy isn’t just an avenue to dignify fortunes — it can also serve as an attempt to influence where society is headed. Over the last half-century, Charles and David Koch made their billions through a chemicals company, Koch Industries, that sells gas and jet fuel and operates oil refineries around the country. They used their money to fight climate legislation and sow doubt about climate science among the American public. But New Yorkers might know them better for the cultural landmarks that bear their names. You can watch ballet at New York’s David H. Koch Theater or, thanks to a $65 million gift, enter the Metropolitan Museum of Art through the David H. Koch Plaza.

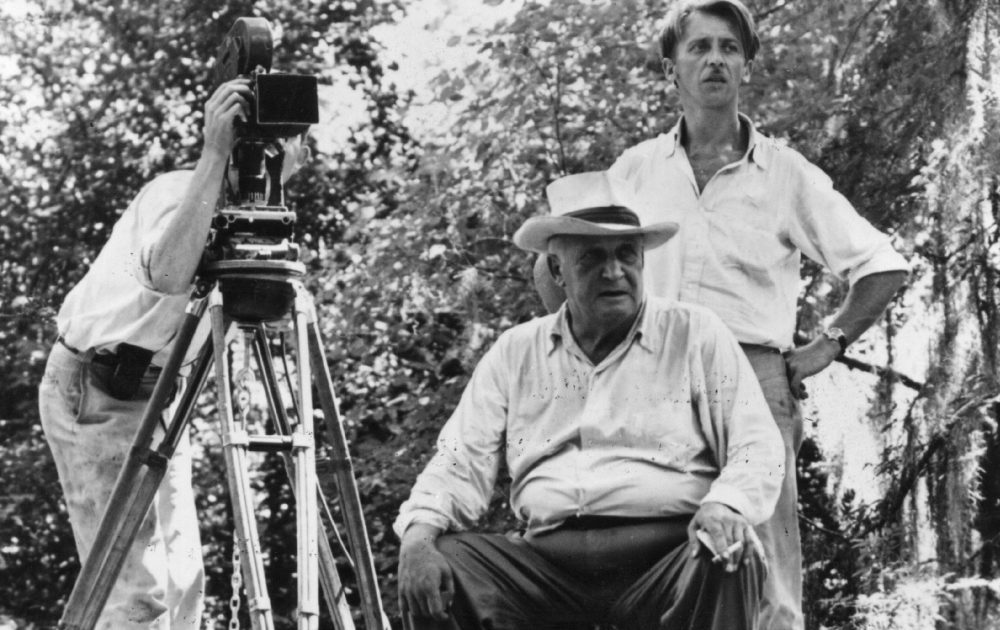

As a corporate donor, Exxon was something of a pioneer. In 1944, the company sent Robert Flaherty, a famous documentary filmmaker, to tour oil fields in Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, and Texas. The resulting fictional black-and-white film, Louisiana Story, tells the story of a young boy in the bayou who questions his father’s decision to let an oil company drill on family land. A few years later, Exxon started sponsoring the New York Philharmonic’s Sunday radio broadcasts.

By the 1970s, the company had become a highly visible patron of museums and symphonies, with an annual arts budget that hit $1.6 million by 1974. “Exxon shows” at the Guggenheim showcased emerging artists from around the world for nearly a decade. Around the same time, Exxon began funding early research on climate change. It didn’t share its findings with the public — instead, it launched an ongoing campaign to spread climate denial and delay action through lobbying and advertising. To this day, Exxon and other fossil fuel companies tout their sustainability efforts while still planning to expand oil production. Activists call this “greenwashing,” and suggest it comes from the same bag of reputation-management tricks as supporting cultural institutions.

A spokesperson for Exxon, Ashley Alemayehu, said in an email that the company’s support for the arts is “part of our support for communities where we work.” She mentioned that most of the company’s support for the arts comes from its foundation’s matching gift program. [Shell declined to comment for this story.]

“They hope that they gain cover,” said Sarah Sutton, who leads the museum sector for We Are Still In, the group of cities, states, tribes, businesses, and other groups trying to uphold the Paris Agreement. “The association with the name and the standing and the trustworthiness of the cultural institution gives them standing that they might not have otherwise earned.”

It can also give them influence. A 2016 report from the U.K.-based group Art Not Oil found that BP’s sponsorship of British arts organizations was hardly “no strings attached.” Through Freedom of Information Act requests, the group discovered that “BP staff have been given opportunity to input into, sign-off, and approve decisions related to programming and content at BP-sponsored institutions” — including helping plan an Indigenous Australia exhibit at the British Museum and getting final say on curatorial decisions.

Flaherty directs the film ‘Louisiana Story,’ circa 1948. Hulton Archive / Getty Images

For a prime example of how fossil fuel funding has shaped art in the U.S., just head to Wyoming, one of the country’s top oil-producing states. Local oil and gas companies and state legislators threatened to withdraw funding for the University of Wyoming over a climate change art installation on campus in 2011, writes Jeffrey Lockwood, a professor at the university, in the book Behind the Carbon Curtain. Chris Drury, a British artist, had installed a vortex of charred logs, 36 feet in diameter, made from pine-beetle-killed trees swirled with lumps of black coal. The piece was meant to explore the connection between coal, climate change, and the spread of pine beetles.

“I hope this isn’t a permanent sculpture,” BP’s director of government and public affairs wrote in an email to the university. A vice president for Peabody Energy passed along this message: “Our $2 million donation to the University is now in question.” The university’s president ordered the installation taken down a year ahead of schedule, right after students left campus after graduation, with “no press planned,” Lockwood wrote.

More often, the ties between museums and oil can lead to self-censorship, said Beka Economopoulos, the cofounder of a pop-up project called The Natural History Museum. “Your multimillion-dollar donor doesn’t have to be in the room to affect the conversation,” she said. A curator might second-guess a climate change exhibit if she’s worried about drawing the ire of major funders.

Three protesters were curled up in the fetal position in the main hall of London’s National Portrait Gallery, wearing nothing but their underwear and a coat of fake oil. It might sound like a bad dream, but it was actually a performance piece protesting BP’s sponsorship of the museum in October.

“Who will there be left to see, who will there be left to paint, if we have no Earth and no people?” one (clothed) protester recited at the event. “We cannot be artists on a dead planet.”

The movement to unhitch art from oil has recently taken off in Europe. Activists from Libérons le Louvre laid black cloth down the steps of the Louvre in 2017, a symbolic river of oil to protest the museum’s sponsorship deal with French oil company Total. The following year, members of the group Fossil Free Culture in the Netherlands were arrested for a demonstration against Shell’s relationship with Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum. The activists sipped dark liquid out of shells, letting the oil-like substance dribble down their white dresses. Then, earlier this year, hundreds of people with banners occupied the British Museum in London, protesting BP’s sponsorship.

These demonstrations have yielded some success. BP ended its 26-year-long sponsorship of the Tate art museums in 2017, and the Van Gogh Museum ended its contract with Shell in 2018. This September, the Royal Shakespeare Company ended a sponsorship deal with BP four years ahead of schedule; and then the National Theater in London announced it was dropping Shell as a corporate member. In November, the Scottish National Portrait Gallery announced it would not be showing an exhibit sponsored by BP.

But many art museums throughout Europe are keeping their Big Oil funding, at least for the time being. The Louvre renewed its relationship with Total, for example, and the British Museum hasn’t budged on BP.

Activists participate in a demonstration outside the Pyramid du Louvre built by Ieoh Ming Pei. SAMEER AL-DOUMY / AFP via Getty Images

In the United States, there’s a patchwork of organizations pushing art museums to sever ties to oil patrons. But if what’s happening in Europe is any sign of what’s coming, protests could be on the way. Susie Wilkening, a museum consultant in Seattle, believes that scrutiny of oil funding will grow as the public becomes more concerned about climate change.

For the most part, the relationship between American art museums and fossil fuel companies remains intact. The Smithsonian Institution, for instance, does not have a rule that forbids taking contributions from companies like ExxonMobil, said Jennifer Schommer, assistant director of public affairs at Smithsonian’s Traveling Exhibition Service, “as long as what is funded is in keeping with our mission.” A spokesperson for the National Gallery of Art said funders don’t influence their programming. “Decisions regarding the museum’s collections, programs, and exhibitions are determined solely by the National Gallery of Art,” said Anabeth Guthrie, the museum’s chief of communications.

Science museums are a different story. The Leonardo Museum, a science and art institution in Salt Lake City, divested from fossil fuels in 2016, following the Field Museum in Chicago and the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. The Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens in Pittsburgh and California Academy of Sciences have also sold off their fossil-fuel investments and instituted new policies that prohibit donations from oil and gas interests.

In the art world, activists have mainly targeted other businesses. Take the Sackler family, owners of Purdue Pharma, the purveyor of OxyContin and major donors to prominent institutions like the Guggenheim Museum in New York. After a wave of negative press tying it to the opioid epidemic, the family announced it would stop giving donations in March. Meanwhile, board members at art museums are getting closer looks for connections to drone suppliers, tear gas used on migrants at the border, and private prisons.

“No money is pure,” said Economopoulos from The Natural History Museum.

It isn’t even clear where the line is between what counts as fossil fuel money and what doesn’t. Donations from oil-industry giants are one thing, but carbon-intensive industries of all kinds sponsor the arts, like airlines and automakers, as well as banks that finance the construction of pipelines and other fossil fuel infrastructure.

John D. Rockefeller poses for Jo Davidson, a noted sculptor. Bettmann / Contributor / Getty Images

There’s also a difference between companies making money from fossil fuels right now and the legacies left by oil tycoons from the last century, like the Gettys and Rockefellers. Some of this old oil money is now being spent to take on climate change and fossil fuel interests. In September, the Getty Trust announced it would invest $100 million in protecting ancient artifacts around the world from conflict and climate change. Aileen Getty, the granddaughter of J. Paul, recently donated $600,000 to the Climate Emergency Fund, which supports youth climate strikers like Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion, a nonviolent civil disobedience group. And the Rockefellers divested from fossil fuels in 2016.

It isn’t clear what would replace fossil fuel largesse if museums and performance venues begin to reject it en masse. Public funding for the arts in the United States has declined 16 percent over the past 20 years, after accounting for inflation. A lot of museums are desperate for money.

“The vast majority, 90 percent of them, struggle to stay open,” said Wilkening, the museum consultant. If more and more sources of funding are considered off-limits, she explained, that’ll be a “legitimate concern.”

There might be an ethical way for museums to take money, she said, but it would come with a lot of stipulations: oversight to make sure the funding is not influencing the board’s choices, and assurances that the money is directly addressing a problem that the donor caused — basically, a form of reparations.

Sutton, with We Are Still In, said she’d take a different approach to separating art institutions and oil money from activists in Europe. For museums, it’s easier to get rid of fossil fuel investments than to ditch a sponsor at the drop of a hat, she explained. “Divesting the endowment is often more navigable,” Sutton said. “There are more tools in place for helping an institution to make that shift. All they need is the political will within the board to make that decision.”

Instantaneously dropping a sponsor, on the other hand, is far more precarious.“There’s no scaffolding to allow that transition to be successful,” Sutton said. “It can only be dramatic.”

One solution that Brown, the New Orleans-based artist, dreamed up is a “fossil free pact” — a collective of cultural organizations that decide to fundraise together, rather than in competition with one another like what happens on the Big Easy’s one-day online giving event, GiveNOLA Day. She thinks that this fossil-free pact would create buzz outside of New Orleans and attract funders from around the world.

With that funding, museums could then use their exhibits to educate people about the effects of climate change where they live and highlight efforts or new technologies to address them. Many institutions have been reluctant to feature climate change in their programming because of a narrower interpretation of their mission and a lack of confidence in the curators’ understanding of climate change, Sutton said. And such an exhibit might lead to blowback from big donors.

In 2018, Brown organized the Fossil Free Fest, an event for artists, funders, and oil industry workers alike in New Orleans. They came together for art, music, film screenings, and workshops envisioning a fossil-free New Orleans. She worked with Antenna, a New Orleans arts organization that’s holding another Fossil Free Fest in April.

After the 2018 festival, Brown said she’s seen a growing public awareness around the role of oil money in New Orleans, as well as the launch of some creative projects pushing back. On April Fool’s Day this year, Antenna trolled the Helis Foundation — the charitable arm of Helis Oil & Gas Company, which plays a big role in funding the arts in New Orleans — with a parody video. It announced a new series of fictitious pro-fossil fuel children’s books sponsored by the made-up “Helix Foundation for the Advancement of Art and Fossil Fuel Culture,” including The Giving Pipeline and One Fish, Two Fish, Dead Fish, Three-Headed Fish.

The organization Healthy Gulf is holding community mapping projects to show what the fossil fuel companies funding the arts are doing to Louisiana’s coast. In response to a series of oil-sponsored murals, they created a map of the oil industry’s activities, labeling “oil wells owned by companies funding arts in Louisiana” and marking oil spills from these companies with caution symbols. At the top, a question is posed: “What if this was a mural downtown?”

If the status quo that fossil fuel companies are protecting continues unchallenged, the world could see 5 degrees Celsius (9 degrees F) of warming over pre-industrial temperatures by 2100, with catastrophic consequences.

But if the keepers of our culture realized their own power, they might ask what would happen if they refused to cooperate. Economopoulos argues that it’s time for museums to go beyond protecting their own collections or cutting their carbon footprint with solar panels and LED light bulbs. Museum officials, she said, “can leverage their expertise and collective voice to support community-led efforts to protect natural and cultural heritage.” She pointed to a solidarity letter connected to one of her projects, which denounced the destruction of sites sacred to the Standing Rock Sioux during the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. The letter was signed by more than 1,400 archaeologists, anthropologists, historians, and museum officials, including many in the arts.

For more mainstream institutions, taking principled stands and shunning big-money donors constitutes a serious risk, but the American Alliance of Museums Code of Ethics suggests that doing so is part of their role in society. The code states that it’s incumbent upon museums “to foster an informed appreciation of the rich and diverse world we have inherited” and “to preserve that inheritance for posterity.” And that’s the quandary facing museums, galleries, and universities today.

“What does it matter if the doors to a museum are open one more year,” Brown asked, “if it’s also underwater?”