1) President Obama rejected the Keystone XL pipeline on Nov. 6.

This is the real, final Keystone decision we’ve all been waiting for. You might have heard that Obama “vetoed” the pipeline back in February, but he didn’t — he vetoed a congressional bill that would have forced approval of the pipeline because he wanted to make the decision himself on his own time line.

2) This is a huge win for the climate movement.

Hardly anyone had heard of the Keystone XL pipeline before Bill McKibben and his climate action group 350.org decided to launch a national campaign opposing it in 2011. If they hadn’t done so, Keystone would have been quietly approved years ago. 350 teamed up with allies who had been fighting the project previously — Native American tribes and farmers and ranchers along the proposed pipeline route, as well as mainstream green groups and grassroots environmental activists — and successfully used the project as a focal point for organizing to fight climate change, staging several high-profile protests in Washington, D.C., and around the country. That tangible focus helped the climate movement grow into a real political force, and today the power of that movement is on display as never before. Put another way: The Keystone fight helped the climate movement grow stronger, and because the movement grew stronger, the fight against Keystone succeeded.

3) Keystone XL is mostly just a symbol.

Which isn’t to say this decision doesn’t matter. Au contraire, it means it matters all the more. To climate hawks, Keystone has come to represent everything society should be moving away from: infrastructure that will enable and encourage extraction of the dirtiest oil on the planet for decades to come. To the oil industry and the “drill, baby, drill” crowd, Keystone has come to represent everything they want to cling on to: more drilling, more piping, continued reliance on fossil fuels. Obama felt so much pressure from climate activists that he chose their side in this epic fight, and that’s a big deal.

4) Still, the Keystone XL rejection will have some real climate impact.

Though its symbolic significance outweighs its greenhouse gas significance, Keystone would have led to increased emissions. It’s hard to say how big those increases would have been, but a study published in Nature Climate Change last year estimated that the pipeline could increase CO2 emissions by as much as 110 million tons per year — or about 1.7 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2012. By way of comparison, Obama’s new Clean Power Plan is expected to lead to a 6 percent cut in total U.S. annual greenhouse gas emissions from today’s levels by 2030, according to calculations by Vox’s Brad Plumer. So the direct climate impact of stopping Keystone is, shall we say, notable but not enormous.

5) Keystone XL is not permanently dead.

Not by a long shot. All 15 of the Republican presidential candidates are in favor of the pipeline and now they’ll be trumpeting its alleged virtues even more loudly and promising to OK it if they make it to the White House. If Canadian company TransCanada resubmits its application to build the pipeline — which would be no small feat of paperwork — a GOP president could promptly approve it. TransCanada has even floated the idea of challenging Obama’s decision under NAFTA.

6) Obama endorsed half of the Keystone XL pipeline in 2012, and now it’s built and pumping oil.

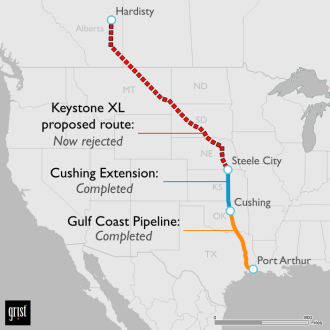

When TransCanada first proposed the Keystone XL pipeline in 2008, it consisted of two parts — a northern leg to carry tar-sands oil from Hardisty, Alberta, down to Steele City, Neb., and a southern leg from Cushing, Okla., down to the Texas Gulf Coast. (The segment in the middle — called the Cushing Extension, stretching from Steele City to Cushing — was already in the works.) In 2012, after activists had targeted the pipeline and gummed up the approval process, TransCanada decided to break XL into two separate projects. The southern leg didn’t cross an international border and therefore didn’t need an OK from the State Department or the White House, so it would be relatively easy to push through on its own. Even though this southern portion, which TransCanada renamed the Gulf Coast Pipeline, didn’t require a stamp of approval from Obama, it got one: During his reelection campaign in 2012, the president came to Cushing, bragged about the expansion of oil drilling and oil pipelines during his first term, and directed his administration to expedite processing for the Gulf Coast Pipeline. It was completed and started pumping oil in late 2013. It was only after Obama won reelection that he started making skeptical noises about Keystone XL — and by then he only meant the northern leg of it.

7) The Keystone rejection does not make Obama a climate hero.

This Keystone XL decision is one highly visible move that Obama made at the behest of very vocal climate activists, but it’s just a small part of the president’s overall record on the issue. He’s done some good stuff to fight climate change: regulating CO2 emissions from power plants for the first time, making cars and trucks more efficient, steering stimulus funds to clean energy, plus lots of smaller climate-friendly initiatives. He’s also been negotiating bilateral climate deals with China and other countries, laying the groundwork for a global climate agreement to be reached at U.N. talks in Paris this December (though there’s no chance the agreement will be as strong as it should be).

On the other hand, Obama has done plenty of bad stuff, from encouraging construction of the southern half of Keystone XL and other pipelines, as mentioned above, to opening up new areas to offshore oil drilling, including the Arctic Ocean, and allowing continued coal mining on public lands. This Keystone move improves Obama’s climate legacy, but he’ll still come out with a pretty mixed bag.

If he wants to burnish that legacy further, he should make a full-court press to ensure the Paris talks are a big success.

—–

Editor’s note: Bill McKibben is a member of Grist’s board of directors.