If you think the fossil fuel industry is “bad,” there’s at least one oil company CEO out there who hears you: Bernard Looney, the recently installed chief of BP.

In a recent interview with the Times of London, Looney said there’s no question that oil — his company’s main commodity — is becoming increasingly “socially challenged.” Even people working within BP started to have doubts about their line of work, Looney said. The company was in danger of losing staff, he said, and job candidates were reluctant to join.

“There’s a view that this is a bad industry, and I understand that,” he told the Times.

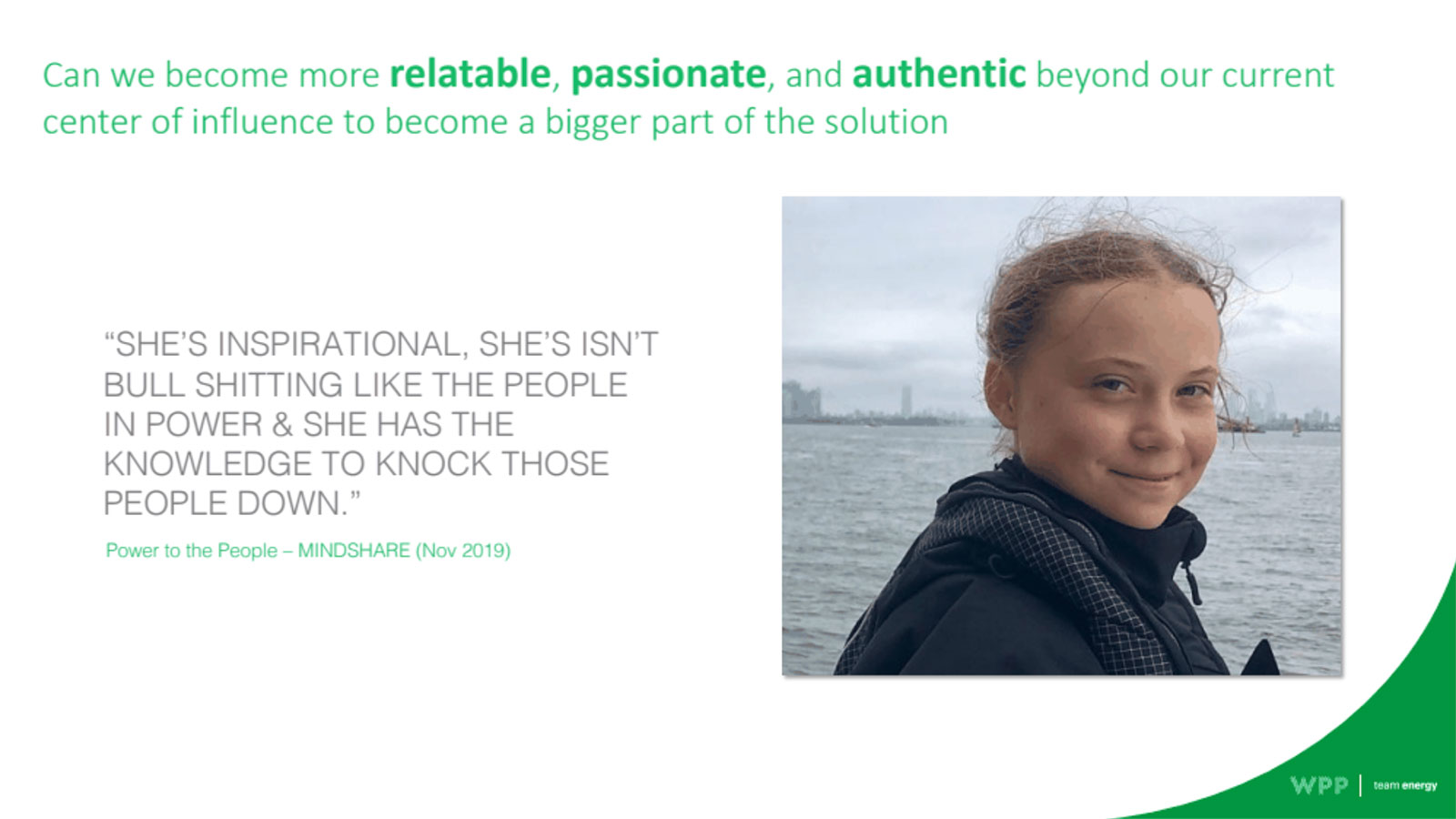

Greta Thunberg, the 17-year-old Swedish activist, and the youth climate movement have presented a public relations challenge for oil companies reckoning with a polluting past — and present. BP has publicly acknowledged the stakes with its new campaign to “reimagine energy,” setting some ambitious carbon-cutting targets. Since Looney came on as CEO in February, the company has committed to going “net-zero” by 2050. Last week, the oil giant announced a new aim that’s a little closer on the horizon, cutting oil and gas production by 40 percent in just 10 years.

That’s one of BP’s responses to oil becoming “socially challenged.” Without those moves, Looney said that the company might have lost many employees. “Good people don’t come to work for a bad company — good people have choices,” he told the Times. “A lot of people are really energized about what we’re doing.”

An internal company slideshow leaked to Drilled News provides more insight into how BP hopes to curry favor with the public, as well as its own employees.

The branding materials, dated January 2020, explain how “the world changed forever in 2019” as millions of people participated in climate protests. Above a picture of Greta Thunberg, the slideshow ponders how the company can become “a bigger part of the solution,” and goes on to muse about how it could win over the trust of Gen Z.

WPP

“How do we signal that we ‘get it’ in a meaningful way so that people can see BP is leading the change?” one slide says.

BP has an uphill battle when it comes to public opinion. Oil is among the industries that the public trusts the least. Just 20 big fossil fuel companies, including BP, are responsible for more than a third of carbon emissions since 1965. And of course there are the catastrophes like Deepwater Horizon in 2010, when BP’s drilling rig exploded and poured 200 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, the worst offshore oil spill in U.S. history.

In the fallout from the disaster, Dev Sanyal, BP’s executive vice president at the time, wrote a document explaining how the fossil fuel industry needed the “social license to operate” to continue its business. That’s industry-speak for the idea that a company needs the public’s approval to stay in business. The phrase comes from the mining industry — its inventor is believed to be James Cooney, an executive at a Canadian gold mining company responsible for an environmental disaster in 1996, when a drainage tunnel in the Philippines burst and sent toxic mud into a river and nearby villages, submerging homes.

Oil companies are worried they’re losing that license. And it might explain why they have been recently trying to get woke. For International Women’s Day in March, Shell Oil announced that one of its women-owned gas stations in California would add an apostrophe to its logo, temporarily becoming She’ll (short for “She will.”) In June, when tens of millions of Americans took to the streets to protest against police brutality and racism, Chevron responded by tweeting that “black lives matter,” stating that “racism has no place in America.”

Long before “social license to operate” had become a phrase, oil companies were concerned about what the public thought of them. The whole field of public relations developed alongside their operations. Early PR whizzes advised the industry to pump out fake news to make sure people heard its version of the story, donate to good causes like the arts to burnish its reputation, and invent fake grassroots groups to advocate for the fossil-fuel cause. Over the past 30 years, Big Oil has poured more than $3.6 billion in reputation-building ads.

But if you look through the spin — yes, there’s still a lot of spin — BP’s promised cuts to oil production are evidence that climate activists are having a real effect on these companies and the future of oil. The reckoning is real.