It’s hard to exaggerate just how much the world changed in just a few weeks this spring. The glittering vehicles that packed suburban office parks disappeared, leaving empty moats of blacktop. Online traffic maps glowed green at what had been reliable deep-red choke points. Families on bikes and delivery trucks moved slowly through newly quiet residential streets. And the fumes from internal combustion engines cleared, with deadly particulate pollution falling by more than half in many cities. The quarantine squeegeed away the smog, leaving sparkling city skylines. The residents of Jalandhar, India, 100 miles south of the Himalayas, had a view of snow-capped mountains for the first time in 30 years.

That plunge in pollution brought with it a drop in greenhouse gases. The state of California, for example, was on track to miss its carbon-cutting target for 2030 before the COVID-19 pandemic. But in a state where transportation is the largest source of planet-warming gases by far, lockdowns triggered large-scale reductions in emissions.

“It was going to be a challenge for California to meet 2030 goals,” said Chanell Fletcher, executive director of ClimatePlan, a California-based advocacy group. “We were not going to do it unless we saw major changes. Well, now we are seeing major changes.”

Of course, a global pandemic is not the catalyst Fletcher wanted and, she added, most benefits are already disappearing as the lockdowns lift. Whenever (or maybe if) the U.S. economy revs up, tailpipes and smokestacks will go right back to belching. Smog is already gathering in China’s cities as the country relaxes restrictions.

Still, elements of this shakeup look likely to stick around. COVID-19 has upended human patterns of movement, and some of those changes will become permanent. But which ones? Will we fall in love with clearer skies? Or fall out of love with transit, worried about the health risks that come with crowded subway cars and buses? This plague could usher in a cycling renaissance and also convince other commuters to suffer through gridlock in the solitude of their cars.

“When we experience traumatic events like this, it exposes our vulnerabilities, and that causes long term changes” said Janna Chernetz, who advocates for getting New Jersey residents out of their cars and onto transit for the Tri-State Transportation Campaign. Superstorm Sandy, for instance, hit the East Coast in 2012, flooding neighborhoods and causing at least $70 billion in damage. “After Superstorm Sandy we realized how vulnerable our infrastructure was and started working to protect shorelines,” she said. “Now the spread of infectious disease is revealing how vulnerable we are when we move from place to place. This will absolutely permanently change us.”

This plague breached the last remaining barriers to working from home like a flash flood sundering dams. Chernetz has noticed how much time she has gained without her hour-and-a-half commute from New Jersey to New York City, and she suspects many other workers are having the same realization:. “People are saying, ‘Shit, I can do my work from home rather than spending three hours of my life every day commuting. Look, during COVID-19 I was completely able to do my job. I don’t need to pay to commute.’”

Before COVID-19, bosses could tell their employees, “No, we can’t make work from home happen,” said Louis Alcorn, a graduate student studying transportation at the University of Texas at Austin. But in the new era, he noted, most bosses won’t have that excuse. Business owners might realize that it can work to their benefit — why spend tens of thousands of dollars every month on a large office space, when you could, say, switch to a smaller, cheaper space and rotate employees week to week?

A nearly empty subway platform at New York’s Herald Square’s subway station in June 2020. Ron Adar / SOPA Images / LightRocket via Getty Images

It’s not often that you can feel a culture changing as it happens, rather than realizing it in retrospect. But as Seders, funerals, and happy hours move online, you can sense the growing comfort with doing it all on a screen. If these trends hold, traffic will shift from subways and bridges to fiber-optic cables. That won’t be enough to solve the country’s transportation problems, but even a small decline in commuters will mean fewer traffic jams, fewer idling engines, and less greenhouse gas emissions.

Unfortunately, it’s not just freeways that emptied. In the subway stations of every major U.S. city, the footfalls of lonely commuters echo. The crowds that surged through turnstiles, paying a few dollars at a time, are gone. In the San Francisco Bay Area, 90 percent of Bay Area Rapid Transit, or BART, riders were staying away through May.

Transit agencies rely on fares, so empty buses and trains destroy their budgets, pushing them deeper into the red with every passing month. BART, for example, lost about $700,000 a day at the fare gates during March alone. Like many transit agencies, BART gets more than half its money from fares. New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority, the country’s largest mass transit system, took in $61 million in fares in May, 88 percent less than what it had expected. “The dip in ridership is really killing transit,” Chernetz said.

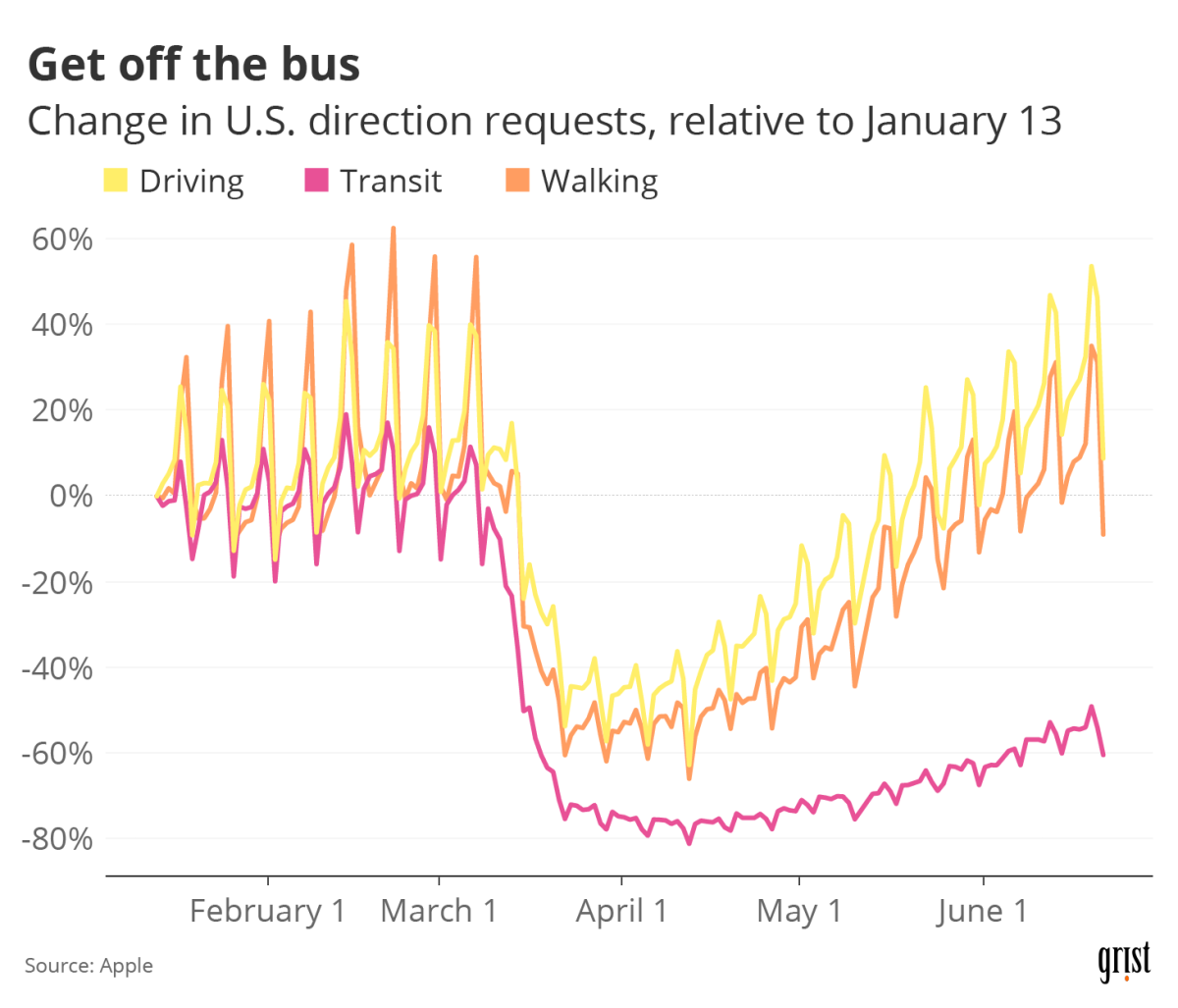

Even though lockdowns are easing in many states, people aren’t exactly rushing back to buses and trains. They’re walking and getting back in their cars. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has asked employers to help workers commute by other means than public transit, such as driving.

Clayton Aldern / Grist

The MTA lashed back against the CDC’s guidance, claiming that transit was still the safest way to get around. “Our transit and bus system is cleaner and safer than it has been in history,” said Patrick J. Foye, chairman of the MTA. But any claims about safety depend on preventing people from crowding: So the MTA and every other major transit agency are asking nonessential workers to stay off trains and buses. And even when transit agencies tell riders it’s safe to come back, people might stay away. In China, as cities re-opened, more people started driving cars, and fewer rode transit.

In places like Phoenix, Arizona, which is just beginning to introduce transit to an otherwise car-centric system, the pandemic could kill those efforts, said Alcorn, the University of Texas grad student. Arizona has recently emerged as one of the country’s hot spots

But in big cities, people will eventually come back to transit to some degree, because there’s little choice. There’s just not enough room for everyone to have a car. “Where there’s tons of congestion you need transit,” Alcorn said. “In large cities, transit is the only way to get around, just geometrically speaking.”

The word “density,” in bold yellow capital letters, looked like a menacing warning light during one of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s coronavirus briefings in early April. New York City, one of the most densely populated places in the country, has been the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak in the United States. After this pandemic, the word “density” will be shadowed by associations with disease and death for some. Some New Yorkers have already begun moving to suburbs. If that trend accelerates, new exurbs will take the place of woods and fields, and local politicians will likely feel pressure to expand freeways as a new crush of commuters battles their way to city centers for work.

The evidence, however, doesn’t support the conventional wisdom that density alone is dangerous. World Bank researchers analyzed the infection rate in 284 Chinese cities and found that those with lower population densities had the most disease. “[W]e can already say with confidence that density is not an enemy in the fight against the coronavirus,” the researchers wrote.

Of course, it’s true that a virus can most reliably spread in places where people are crowded together closely enough to breathe in each other’s respiratory droplets. If you can isolate yourself in a desert fastness or a mountain aerie, that’s a surefire way to keep yourself COVID-free.

As a result, there are big empty stretches of America with very few cases. But if you look at the maps showing infection rates across the country, it’s clear that rural areas aren’t protected. The sparsely populated Navajo Nation has more COVID-19 cases per capita than New York state. Perhaps it was a church meeting that triggered the spread there, combined with small, multigenerational homes, and a population that has to leave the house to work. There are also high infection rates in places like Cass County, Indiana, Lincoln County, Arkansas, and Lake County, Tennessee. All of these spots technically have low density, but they crowd people together in a few small homes, in meat-processing plants, or in prisons.

“For people who have the means, it’s easy to believe we’d be better off alone,” said Shoshanna Saxe, who studies sustainable infrastructure at the University of Toronto. “But the association is with poverty, not with density.”

Manhattan is New York City’s densest borough and home to nearly all of the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods. Despite its more than 65,000 people per square mile, the borough just happens to be the safest place to be in New York when it comes to the virus. Some of the world’s most populous cities have been heralded for how well they’ve handled outbreaks: Seoul, Hong Kong, and Singapore have shown that a stringent public health response can successfully quash the virus’s spread, Saxe said. In the absence of such a response, as in Manhattan, wealth can serve as a prophylactic, allowing people to stay home, telecommute, and simply have anything they need delivered.

In other words, the problem isn’t population density; it’s too many people forced to share the same space (what’s called internal density). A city can be safe if you are in a condominium, and a home in the rural countryside can be dangerous if you are crammed in with a dozen other slaughterhouse workers. Your risk of infection depends not on the number of people living close by, but on whether you can isolate yourself. That’s part of the reason why nursing homes were an early hot spot.

“Grocery stores in suburbs are very dense, a bar is dense, schools, and places of worship are dense,” said Costa Samaras, who studies transportation and energy at Carnegie Mellon University. “If density is a problem, then people gathering is a problem.”

An apartment complex resident stands at his window during the COVID-19 pandemic in Downtown Los Angeles. Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times

But the perception that density fosters the spread of disease will be hard to debunk. And that fear is likely to prove useful to those who don’t want to see new apartment buildings in their neighborhoods stocked with single-family homes — a change that makes for more efficient, sustainable cities. If these NIMBYs succeed, it would push new housing farther away from city centers, ultimately forcing low and middle-income people into long commutes that compel families to buy cars, thus generating more emissions.

“I’ve started hearing people have been talking a lot about how sprawl is good all of a sudden, but good for who?” said Fletcher of ClimatePlan. “It forces you to drive, and you might not have access to a reliable car.”

Who could forget the first week of June 2017, the Trump administration’s inaugural “infrastructure week?” Apparently nearly everybody (except those making sport of it).

Pleas for funding most sensible forms of transportation infrastructure funding have gone unheeded for decades, and over the past three years, the reappearance of “infrastructure week” is now more punchline than policy proposal — a symbol for the way partisan ire can stop even the most non-partisan ideas. Then the pandemic showed up this spring and, in a flash, Congress handed $25 billion to transit agencies. More is likely on the way.

The pandemic is crashing transportation systems, but sometimes a crash shakes things up enough to create the opportunity for genuine change. In a national crisis, the gridlocked norms of policy-making sometimes vanish, allowing Congress to do things that once seemed impossible. And as members of Congress begin crossing the aisle to pass stimulus bills, it’s clear that we are entering one of those rare moments.

There are many good reasons for the government to improve the country’s transportation networks. Restarting the economy means people will need to start moving again, often in cars, because not everybody can work from home. There are plenty of creaking bridges, roads, and public facilities like water treatment systems that need repair: The United States faces at least a trillion dollars in repairs, according to an estimate by the Volcker Alliance. Fixing them creates jobs.

“If governments go looking for “shovel-ready” projects then it’s going to be business as usual,” said Saxe from the University of Toronto. That means building more overpasses and cloverleaves for cars — moves she would consider mistakes. “It’s really expensive to build infrastructure for cars, and even more expensive if you consider the costs to the environment.”

A more enlightened spending package that redirected even a smidgen of the more than $40 billion of federal funds for highways each year could dramatically expand bus and rail lines. According to a Harvard-based study, the longer someone spends commuting, the worse their chances of escaping poverty, said Joshua Stark, a policy director for TranForm, an advocacy group in Oakland, California. “If the bus service isn’t reliable, you are going to be standing at the stop thinking, ‘Is it worth it to be 15 minutes late to work again, or am I just going to plunk down a grand on a 1990 Civic?’” Stark said. Buy the klunker, and it will immediately begin siphoning money for repairs and fuel.

Stark said we need to scale up bus service to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from transportation, the top source of U.S. emissions. Others see a chance to try something new. Kara Kockelman, who studies transportation engineering at the University of Texas at Austin, said it might not make sense for small and mid-sized cities to rely on more buses and trains. Big cities simply grind to a honking halt without transit, but in places with less congestion, it might make more sense to incorporate ride-sharing services like Uber and Lyft into the mix. If those cars are electric, it could be a climate solution. Put up a curtain, or a plexiglass barrier between the driver and passenger, and you have a relatively safe, low-carbon way to ferry people around.

“There are an awful lot of transit agencies running really large vehicles practically empty,” Kockelman said. Bus lines and trains aren’t nimble. They run on fixed routes and schedules, whether anyone needs them or not. In the future, Kockelman said, they could learn from the Lyfts of the world and provide rides “only when they’re needed.”

But what are big cities to do? They simply don’t have the space to move everyone by car. Alcorn, Kockleman’s graduate student, who has researched transportation in Lagos, Nigeria, said that after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, people eventually went back to the buses and minivans that form the mass transit system. Virus or no virus, there are only so many cars that can fit on roads before everybody gets stuck in gridlock. To avoid an explosion of coronavirus cases as people return to subways, many cities are trying desperately to get people to walk, or ride bikes.

Cities from New York to Oakland have closed miles of roads to cars. London is closing streets, adding bike lanes, and widening sidewalks to prepare for a 10-fold increase in cycling and a five-fold increase in pedestrian traffic as people return to work. That’s because social-distancing rules — likely with us for a while — have dramatically reduced the number of people who can fit on the buses and railways. “This is the biggest transformation of London’s streets ever,” Mayor Sadiq Khan told the BBC. And it goes beyond Britain’s capital. Prime Minister Boris Johnson, a veteran bicycle booster, has heralded “a new golden age for cycling,” with his government recently announcing plans to spend £2 billion ($2.5 billion) to build bike paths and walkways.

People wearing protective masks walk their bicycles past a social distancing sign reading in Central Park during the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo by Dia Dipasupil / Getty Images

It takes years to build a new bridge or dig a new subway tunnel, but cities can reallocate street space immediately: A line of traffic cones and some paint can turn a parking lane into a bigger sidewalk. “And those changes are not something that needs to go away after the pandemic,” ClimatePlan’s Fletcher said.

In most cases, cars will eventually return to those streets, because it’s just as easy to remove those traffic cones and satisfy drivers hunting for parking spots. Some cities, however, are already making the pedestrian-friendly changes permanent. Milan is taking the opportunity to widen sidewalks and add bike lanes on 22 miles of roads. Paris, which had been mulling adding more bike lanes for years, has stepped up the process to add 400 miles of bicycle lanes throughout the city.

In the United States, bicycle sales have surged, with many shops selling out their inventory as people seek out a two-wheeled way to get around. New York has witnessed a bicycling boom, and New Jersey has seen many families “buying bikes so they can ride with their kids,” Chernetz said. As more people figure out how to make their way around big cities walking and biking, especially where parking spots were already scarce, they might discover that there are lots of errands to run within a mile of their home — a trip to a drug store or the train station — that can be easily accomplished without four wheels.

Carnegie Mellon’s Samaras said one unsexy idea could yield big benefits: new delivery vehicles. The importance of moving goods from supplier to shop was underscored when toilet paper, cleaning supplies, and other in-demand goods vanished from store shelves in March. “We don’t usually think a lot about supply chains, but right now everyone can see they are literally lifelines,” he said, “but they run on diesel, gas, and jet fuel.”

It used to be that the government had to buy fossil fuel-powered heavy vehicles because there wasn’t another option. That’s recently changed. At the start of the year, UPS committed to buying 10,000 electric delivery vehicles; not long after Amazon ordered around 100,000. Buying a new fleet of electric trucks for, say, the struggling U.S. Postal Service could help the economy and the environment. “That would be really good stimulus,” Samaras said.

Americans are developing a lot of new habits that are likely to stick around. Some are small-scale changes that mirror trends in the larger economy. In an effort to protect bus drivers from passengers standing too close while they fumble with their change, transit systems in Seattle, San Francisco, and Houston have stopped charging fares and asked riders to board at the rear doors. That probably won’t last. But eliminating coins could do more than keep a safe distance between drivers and riders. Stark from TranForm said wholesale adoption of touchless transit passes would help speed buses along their routes and make it easier to transfer from to trains. “If we could move away from the concept of fare collection at every stop, then in the long run that would be a real benefit,” Stark said.

People might also decide they want to keep breathing clean air, now that they’ve tried it. “Cities could say, ‘We’ve seen what blue skies look like, here’s how we could keep them,’” Samaras said. “That’s both a realistic and necessary goal. But we can’t do it by having everybody stay home.”

A society doesn’t get to choose its disasters. But it can decide how to react to them.

“The important thing to realize is that we get to choose,” said Saxe, the infrastructure expert. “We don’t have to run and hide. We can choose a better future, or we can double down on past mistakes.”