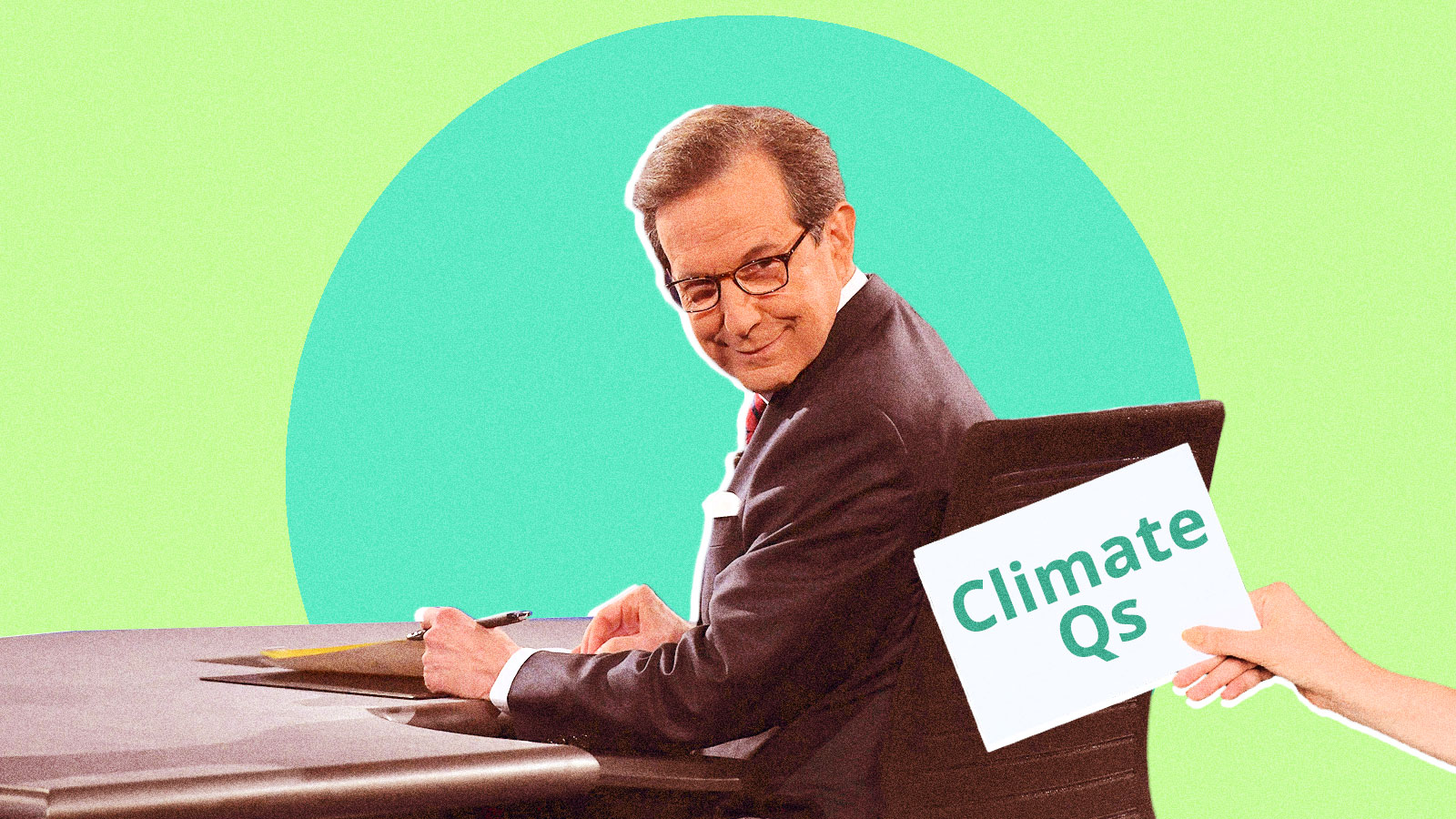

Next Tuesday night President Trump and Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden will travel to Cleveland, Ohio, to square off in the first of three presidential debates. Fox News anchor Chris Wallace will moderate, and he’s already chosen his six topics for discussion.

They are: the records of the two candidates, the battle to replace Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s seat on the Supreme Court, election integrity, issues surrounding race and violence in U.S. cities, the once-booming-now-busted economy, and of course the six-month-old COVID-19 pandemic that has cost 200,000 Americans their lives.

Notice a glaring omission? We do. Climate change is nowhere to be found, despite weeks of news about wildfires in the American West and a hyperactive Atlantic storm season that’s already whizzed through the English alphabet.

Lawmakers noted the climate’s absence, too: In an effort spearheaded by Massachusetts’ Democratic Senator Ed Markey, on Wednesday 37 U.S. Senators — 35 Democrats and Independent Bernie Sanders — wrote to the Commission on Presidential Debates, imploring that the climate crisis receive greater attention during this debate cycle. “The climate crisis isn’t coming, it’s here,” they wrote, and voters want to the candidates to talk about it. A poll released this week found that 74 percent of voters want climate questions to be asked during the three presidential debates.

Even with no changes to Wallace’s debate agenda, our warming planet could still come up in the first debate. As we at Grist attempt to prove daily, climate has links to nearly all other issues in the election, including COVID, Trump’s and Biden’s records, and of course the economy. Don’t believe us? Keep reading.

The Trump and Biden records

For years, American presidents have used their executive powers to shape environmental policy, and President Trump is no exception. Since 2016, he has used his office to pursue a business-friendly, deregulatory agenda, rolling back at least 68 of the country’s environmental and climate-related policies.

Biden of course can’t cite the same presidential experience, but as vice president he supported the Obama administration’s use of executive orders to implement a climate agenda, which included the Clean Power Plan. Biden also can point to his decades-long career in the Senate — during which, all the way back in 1986, he introduced the Global Climate Protection Act, the chamber’s first climate change bill.

Both Trump and Biden have pitched themselves as climate candidates — the former is claiming to be the “No. 1 environmental president,” while the latter is promising that he can lead the fight against climate change.

The Supreme Court

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death on Friday vaulted the topic of Supreme Court nominations into the spotlight as a major campaign issue. Among the many legacies the late and “notorious” justice leaves was her support for environmental policies. According to Politico, she was a consistent vote in favor of clean air and water regulations and emissions controls.

Her successor, who will ultimately be chosen by either Trump or Biden, may be poised to help shape decades of environmental policy — especially as the Court considers weighing in on an increasing number of lawsuits that states, cities, and counties have filed against fossil fuel companies for their contributions to warming.

COVID-19

The pandemic and the climate crisis share many of the same roots. Deforestation and habitat destruction are obviously bad news for the environment — but they can also make a “disease-emergence event” more likely by pushing wild animals into closer contact with humans. When that happens, animal diseases can make the jump to us. Scientists say this is what likely happened with the coronavirus.

There’s nothing we can do about SARS-CoV-2 now, but much as world leaders can take action to prevent aspects of climate change, they can also implement policies to prevent future pandemics from cropping up. That might mean curbing urban encroachment on wild spaces, but it can also mean addressing factory farms in the U.S., which scientists have long said are “a hotspot for emerging pandemics.”

The economy

After six months of COVID lockdowns (and still no end to the pandemic in sight), much of the candidates’ plans for the economy will involve some sort of recovery from the coronavirus-induced recession. Climate advocates like the group C40 Cities have called for a plan that prioritizes sustainability and environmental justice. That might mean investing in green jobs, public services, mass transit, and retraining programs for workers in the fossil fuel industry.

In July, Biden made clear he saw the creation of a new clean energy economy as a part of the recovery from COVID. He unveiled a $2 trillion plan that over four years would invest heavily in transitioning the U.S. to 100 percent carbon neutral electricity by 2035, shifting the government fleet of vehicles to electric, and funneling 40 percent of energy infrastructure improvements to vulnerable communities. As vice president under President Obama, Biden oversaw the implementation of the 2009 Recovery Act, which included more than $90 billion in clean energy investments.

Race and violence in our cities

It’s impossible to talk about racial justice in the U.S. without also looking at the conditions in which many communities of color live. From air pollution to tainted water to toxic chemical exposure, environmental impacts fall heavily along racial and economic lines, with low-income Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous communities facing greater harms than their more affluent, white counterparts. And the effects of climate change — including sweltering urban heat and rising sea levels — are set to cause disproportionate economic damage to these communities as well.

Addressing racial inequities in America’s cities also addresses the climate crisis, sparing vulnerable communities from the pollutants that exacerbate warming and pulling them off the frontlines of climate change.

Election integrity

The compounding crises of COVID-19 and calls for racial justice have brought to light serious concerns about the integrity of the presidential election — specifically, people are worried about systemic voter suppression. Many past policies have worked to limit Black, Brown, and Indigenous people’s access to the ballot box, yet these are the same demographics who stand to lose the most from climate change.

Relatedly, these groups consistently rank global warming as a greater concern than their white counterparts. They may be more likely to vote based on a candidates’ position on climate change — and disenfranchising them could thwart the public’s interest in taking climate action.

So, it’s fine, Mr. Wallace, that climate didn’t make into your top six issues. But it should be clear from what’s written above that there’s no real excuse for warming to go unmentioned during your 90 minutes with President Trump and Vice President Biden.