What is there to say about 2020 that hasn’t already been said? It was the longest, the hardest, the darkest — and, on top of everything else, full of bad climate news. The Trump administration continued its steady assault on environmental protections even as the COVID-19 pandemic devastated the country. Despite some late-breaking clean energy funding in the U.S., global stimulus spending devoted far more money to fossil fuels than renewable energy. The dip in emissions brought on by the pandemic was just that — a dip.

But we’re here to tell you that this year wasn’t a total wash. Even during a global pandemic, with powerful forces working against it, momentum toward a less fiery future kept pace. Please, join us in taking a look back at six ways climate action moved forward this year.

1. Climate change was a major election issue

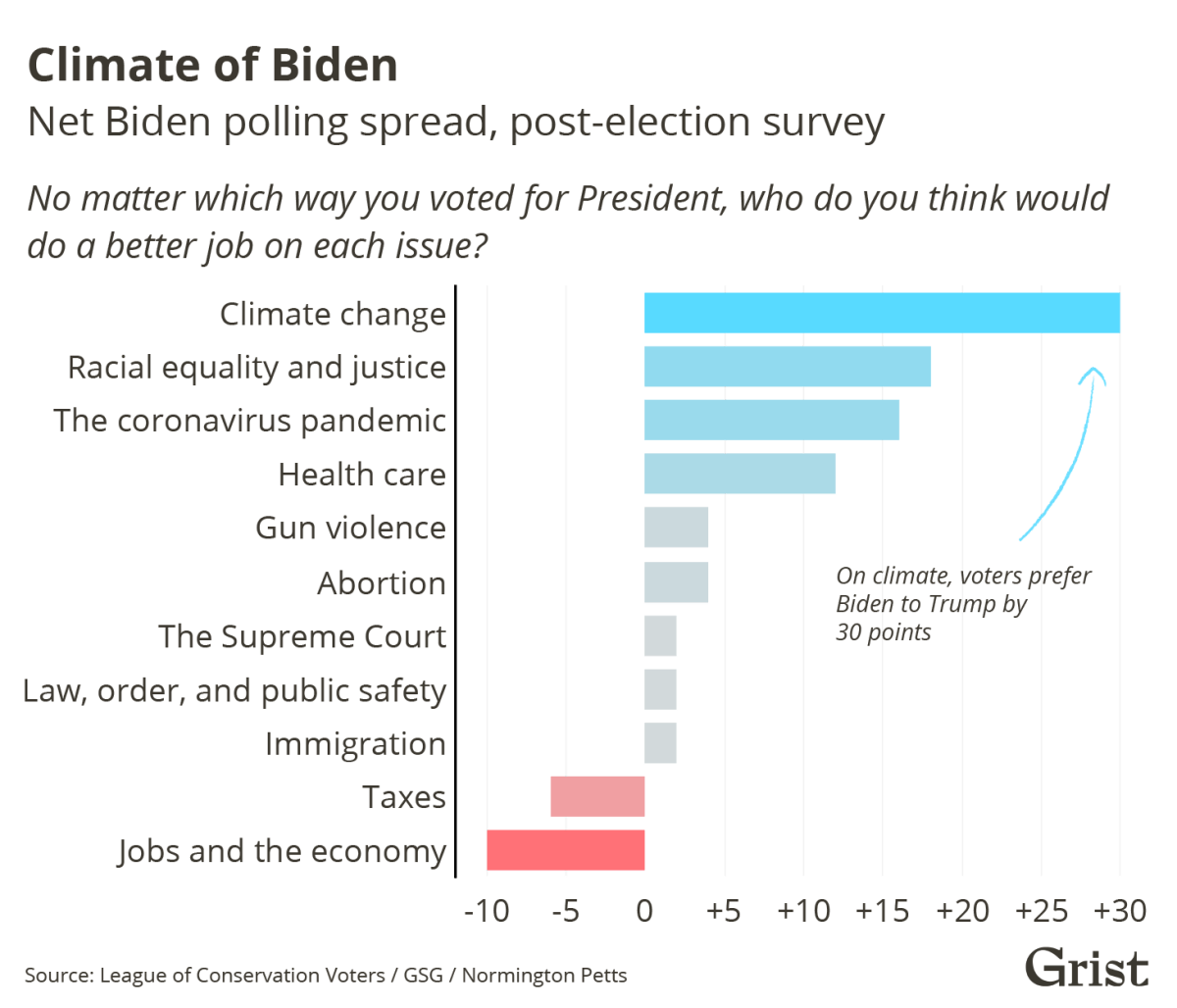

2020 was the year climate change finally entered the political spotlight. Look no further than the Democratic primaries, where dozens of candidates competed for the title of fiercest climate hawk and tried to one-up each other with progressively more ambitious climate plans. (Senator Elizabeth Warren wowed voters by producing 14 separate documents outlining her climate agenda, but the title of “most ambitious climate plan” still goes to her Senate colleague Bernie Sanders’ $16 trillion “Green New Deal.”)

The one-upmanship continued even after Joe Biden had clinched the Democratic nomination, when Biden unveiled an updated and more aggressive version of his primary climate plan. And he doubled down as the general election drew nearer — Biden released three climate-themed ads in the weeks leading up to November 3 and made history by saying he’d “transition the oil industry” at the final presidential debate in October.

Why did presidential candidates bend over backward to show voters that they’re serious about climate action? Because polls show that climate change matters to Americans. A lot. Ahead of the election, a national survey showed that 58 percent of Americans were either “somewhat concerned” or “very concerned” about their communities being affected by climate change. Exit polls from the League of Conservation Voters showed that, among conflicted voters (those who considered voting for both Trump and Biden), Biden was preferred over Trump on “climate change, clean energy, and the environment” by a 58-point margin.

2. Big institutions pledged to pull their cash out of fossil fuel companies

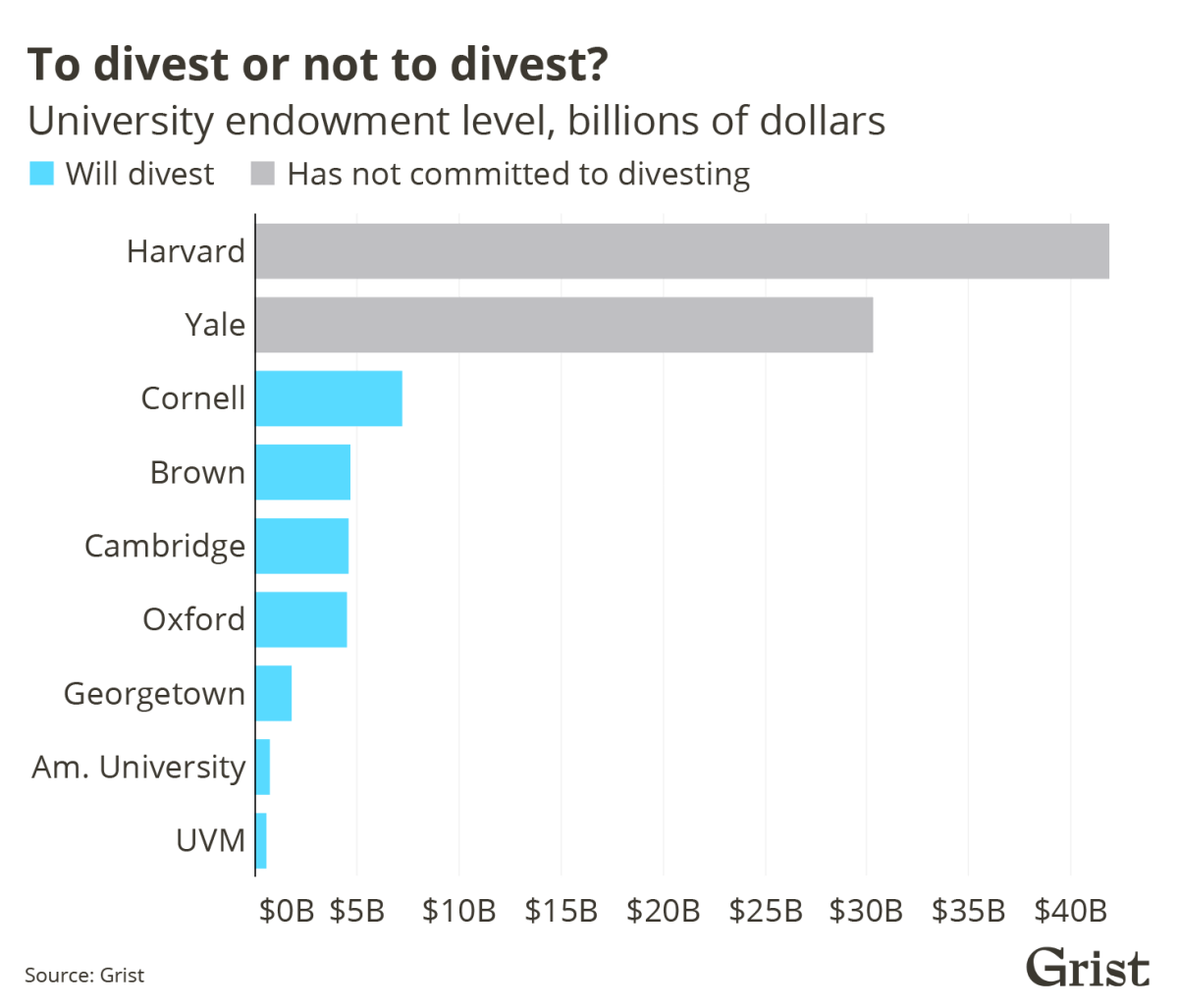

Fossil fuel companies lost a lot of money this year, and not just because of the drop in demand for oil and gas caused by the pandemic. The divestment movement scored major wins as schools, faith institutions, and cities all over the world made new pledges to pull their investments from companies that extract and sell fossil fuels.

Prestigious schools like Oxford and Cambridge in the U.K., and Georgetown, Brown, American University, and Cornell in the U.S., joined a growing list of colleges and universities planning to divest their endowments from fossil fuel companies. Pressure mounted on two of the wealthiest universities in the country, Harvard and Yale, which have a combined endowment of $72 billion, as divestment activists ran for open seats on the boards that oversee the teams that manage how their endowments are invested. And while neither school committed to divestment, Harvard is dipping its toes in the concept with the announcement of a still-vague plan to bring its endowment to net-zero by 2050, arguing that it will be able to work with fossil fuel companies to achieve it.

Activists weren’t happy about that, but they did celebrate when the $226 billion New York State Common Retirement Fund, the third-largest public pension fund in the U.S., announced it would basically do the same thing by 2040. The main difference was that Tom DiNapoli, the state’s comptroller, laid out a detailed roadmap for how he would achieve net-zero, including a pledge to divest from companies that aren’t preparing for a low-carbon economy. He’s already eliminated 22 coal companies from the fund.

Whether divestment promotes the broader changes needed to decarbonize the economy is still debated. But what became more apparent in 2020 is the risk of maintaining investments in companies that aren’t ready for those changes, which are happening regardless. Exxon, which hasn’t made any commitment to reduce its total emissions, did so poorly this year that it got booted from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, an influential benchmark of top stocks. So if you have money in index or mutual funds, there’s a chance that you’ve divested some of your own savings from fossil fuels without even knowing it.

3. Renewables kept growing despite the pandemic

Fossil fuel companies took a catastrophic hit this year when the COVID-19 pandemic ground the economy to a standstill and sent oil prices tumbling. But the renewable energy industry proved to be far more resilient.

Skies clear of smog and other pollutants gave solar panels a boost this year, especially in the U.K., where the uptick in solar power efficiency helped the country run on zero coal-fired power plant generation for more than two months for the first time in over a century. And on this side of the pond, electricity generated by solar, wind, hydro, and other renewables outpaced electricity generated by coal for 40 days straight.

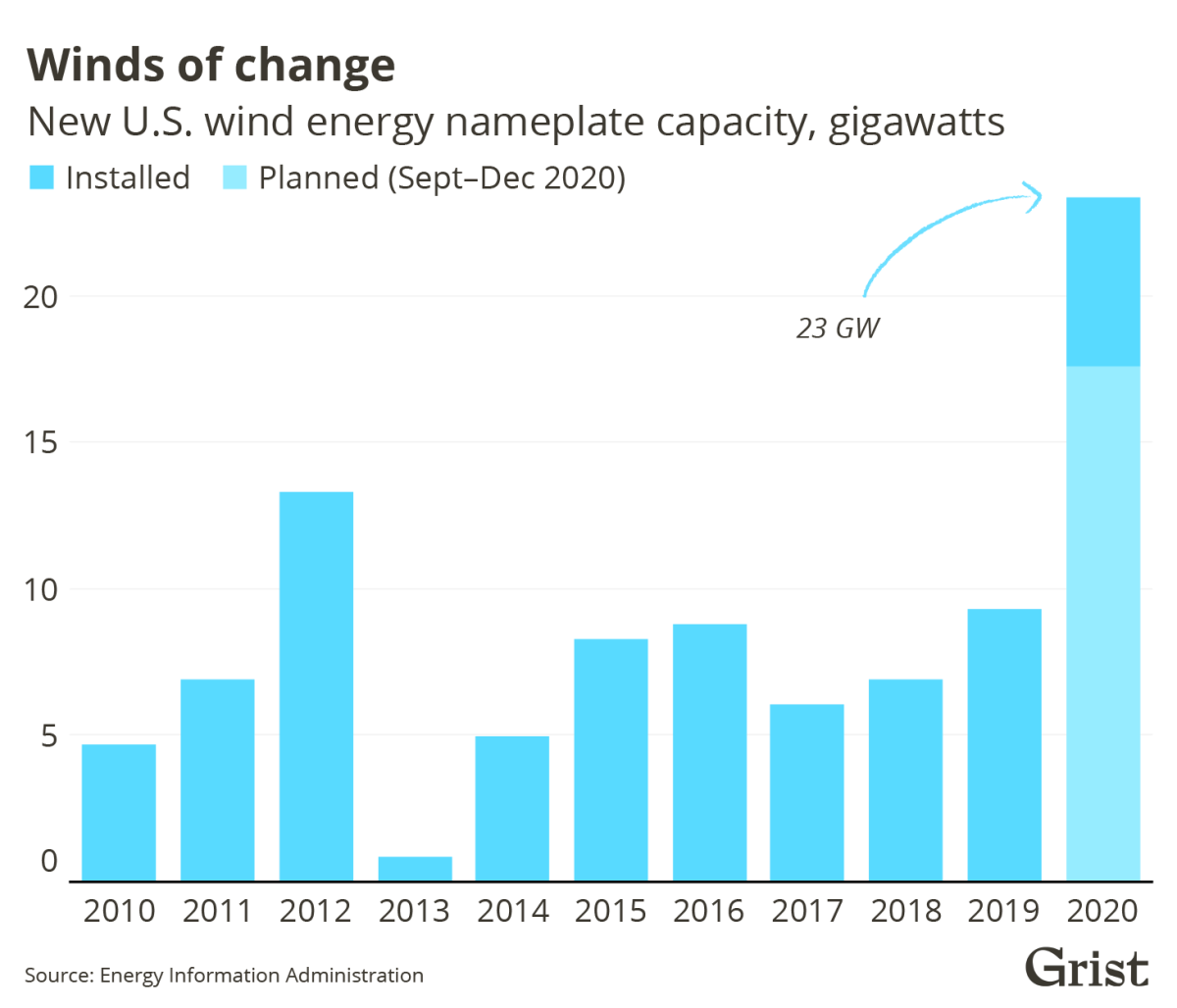

In November, a report from the International Energy Agency projected that renewables will account for 90 percent of the new power capacity added to grids worldwide in 2020. A different report from the global research and consultancy firm Wood Mackenzie, published in December, found that U.S. solar installations are expected to grow 43 percent this year.

Renewables are still getting cheaper, too. A study by clean energy research firm BloombergNEF found that solar and onshore wind power are the most affordable new sources of electricity for two-thirds of the world’s population. The price of electricity from onshore wind farms dropped 9 percent since mid-2019. And falling costs, more efficient technology, and government support in some parts of the world have fostered larger renewable power plants, with the average wind farm now double the capacity it was four years ago.

To boot, polling on how Americans think about energy sources like solar and wind remained consistent this year: The vast majority of Americans say developing alternative sources of energy should be prioritized over developing fossil fuels.

4. Pipelines became nearly impossible to build

Pipeline or pipe dream? Pipeline construction companies and the energy companies paying them to create the infrastructure to transport oil and gas across long distances ran into roadblock after roadblock this year. So many roadblocks, in fact, that some energy companies just gave up trying to build them.

That’s what happened to the Atlantic Coast Pipeline over the summer: The U.S. Supreme Court gave the pipeline the green light to cross under the Appalachian Trail, but a few weeks later, Dominion Energy and Duke Energy, the lead developers of the project, decided to take a hike and dump the pipeline altogether.

The Dakota Access Pipeline, the approval of which sparked the protests at Standing Rock in 2016, also took a critical hit over the summer when a federal judge said the company behind the project, Energy Transfer, and the Army Corps of Engineers had failed to conduct a sufficient environmental review. The judge ordered the pipeline to shut down while the review was conducted. An appeals court swiftly overturned that order, but the company and the Army Corps still have to conduct the environmental review. When Biden takes office, he could opt to shut down the pipeline entirely.

Speaking of Biden, the president-elect has promised to shut down the Keystone XL pipeline by revoking the presidential permit President Trump granted the project in 2019. TC Energy, the company building the project, has already built some 120 miles of pipeline since last spring, but if Biden makes good on his campaign promises (and green groups expect him to), he could put the kibosh on Keystone XL after he’s inaugurated.

More pipelines were put on the chopping block this year: The Mountain Valley Pipeline is struggling to keep construction going as judges keep tossing out crucial permits, forcing the company to hunt down new ones. Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer delivered a serious blow to Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline in November, ordering it shut down. Enbridge filed suit against Whitmer, arguing that only the federal government has the jurisdiction to shut down pipelines, but the incoming Biden administration can reaffirm Whitmer’s authority and take other steps to stymie Enbridge’s plans.

5. Cities put a check on emissions from buildings

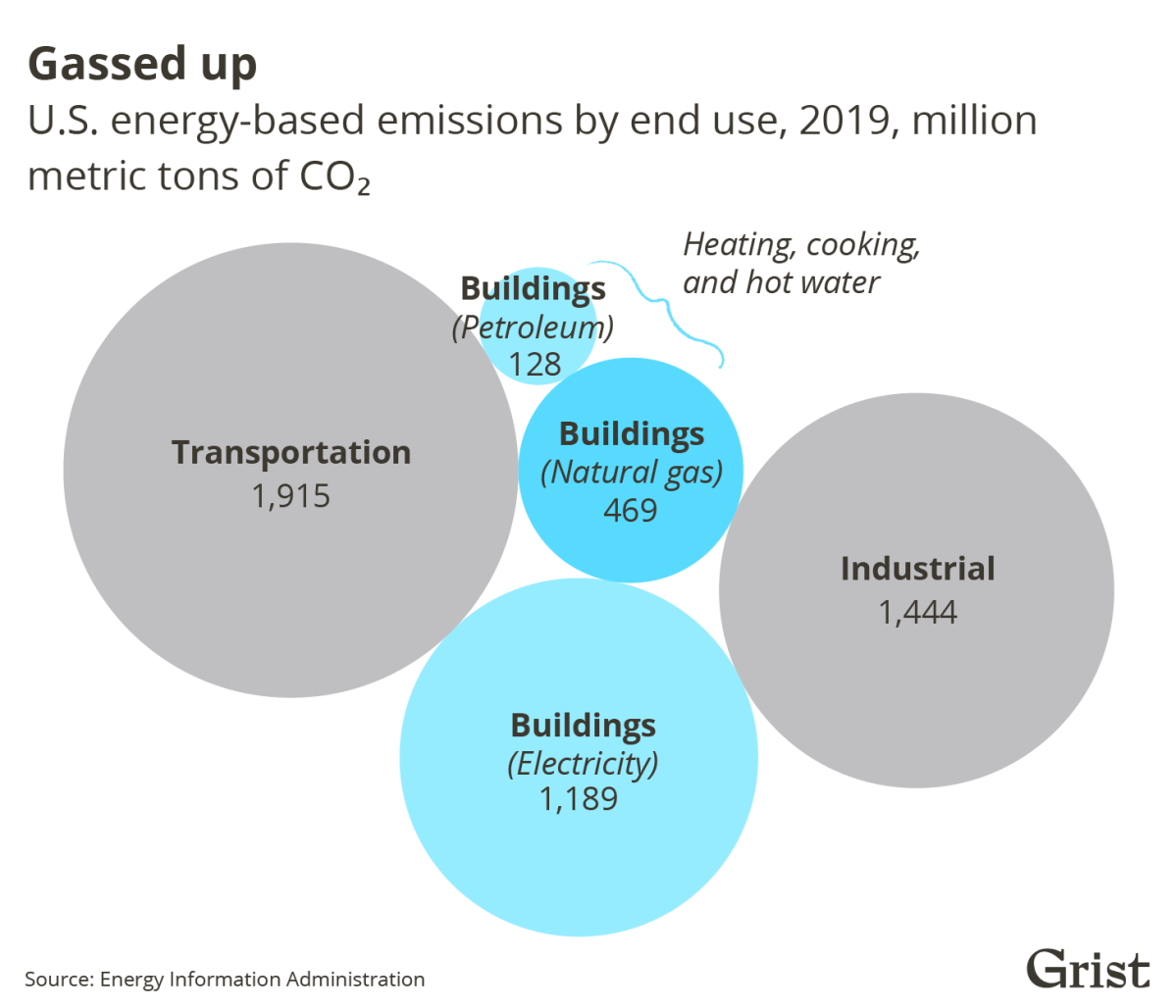

A recent United Nations report found that the carbon emissions from heating, cooking, and using electricity in buildings hit an all-time high last year and were responsible for 28 percent of global energy-related CO2 emissions. Fortunately, in 2020, efforts to rein in emissions from buildings took off.

Just a few weeks ago, the cities of San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose passed laws limiting the installation of appliances that run on natural gas in new buildings, joining 37 other jurisdictions across California that have already done so. These “gas bans” have been catching on around the country: Seattle’s mayor wants to update the city’s building code to prohibit the use of fossil fuels in new buildings; St. Louis has new building performance standards that will effectively phase out gas appliances in larger buildings; and Brookline, Massachusetts, has petitioned the state to let it ban gas hookups in new buildings after an earlier effort to do so was found to conflict with state laws.

In December, Washington state proposed what could be the nation’s first state-level gas ban, and several new state climate action plans and task forces, including in New Jersey, Michigan, Nevada, and Maryland, explicitly mentioned the need to electrify buildings.

But as the idea of moving away from gas in buildings gained currency, some states ran in the opposite direction. Under pressure from industry, lawmakers in Arizona, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Tennessee passed nearly identical bills this year that prohibit their own municipalities from banning gas.

To be clear, decarbonizing buildings is not as simple as banning gas hookups or appliances. As more buildings go fully electric, gas utilities could undergo a slow death spiral, and fewer and fewer customers could end up paying to maintain a vast network of gas pipelines. But states are finally reckoning with these questions — New York, California, Colorado, and Massachusetts all opened new investigations this year into the future of gas distribution to try to answer them.

6. The world agreed on achieving net-zero by mid-century

The idea of “net-zero emissions” has been around for years, but in 2020, it was thrust into the mainstream as an essential tenet of climate policy around the world.

Every week seemed to bring a new announcement of a state, country, bank, utility, tech giant, or even oil company promising to get to net-zero over the next few decades. Generally, that means they’ll get to a place where their net emissions, between the CO2 they release into the atmosphere and the CO2 they suck out of it through natural and technological means, are zero. Microsoft even said it would go beyond that point to “carbon negative” by removing all the carbon it has emitted since its founding in 1975.

In theory, net-zero is a valiant goal — a 2018 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said that the world needs to get to net-zero by 2050 in order to avoid the catastrophic effects expected to occur if the globe warms more than 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F).

But that conclusion was based on a crucial premise: First we have to dramatically reduce emissions. The whole “net” part of the deal should really only apply to the parts of the economy that are hardest to decarbonize, like aviation and shipping. But many of the net-zero pledges made this year by companies are nebulous about when they will reduce their emissions, or whether they’ll do so at all. The energy companies with net-zero pledges are still expanding the fossil fuel side of their businesses, and many of the tech companies with net-zero pledges are still helping those energy companies find and extract more fossil fuels.

The most important development in 2020 may not have been the slew of net-zero pledges, but something a little more obscure. Companies finally began publicly accounting for the emissions tied to their supply chains and the products they produce, known as “scope 3” emissions. Transparency around scope 3 puts more pressure on reducing emissions throughout the economy.

Next year, we’ll be looking to see which companies shore up their pledges with near-term targets and which ones show up in Washington to lobby for the policy changes that will help them deliver on net-zero.